Webinar recap: Charrettes go virtual

Last week, we hosted “Charrettes go virtual: Missoula, Montana hosts an online charrette to advance a community vision,” a joint webinar between the Form-Based Codes Institute and the National Charrette Institute. Speakers discussed a first-of-a-kind fully virtual community engagement process conducted for the Mullan Area Master Plan. A recording is now available.

Local planners and design experts had long planned a week’s worth of face-to-face workshops with residents, decision-makers, business owners, environmental advocates, and more to design the future of the Mullan Area—the western edge of rapidly growing Missoula, MT. But as stay-at-home orders and social distancing guidelines fell into place in March, it became clear the intensive community design workshop—known as a charrette—couldn’t proceed as planned.

After careful consideration, which included the discussion of a soon-to-expire BUILD grant for infrastructure in the project area, city leaders and consultants Dover, Kohl & Partners (DKP) decided to move the collaborative effort entirely online. The last-minute pivot to engage stakeholders through a Virtual Charrette Hub, which housed dozens of collaborative online meetings, virtual design studios, and a 24/7 feedback portal, became the first of its kind—and a wild success.

Not everyone has the time, resources, or technical ability to engage online right now. In many cases, communities should consider postponing community engagement to a later date to be more inclusive. But Missoula’s case was different—months of in-person engagement preceded the online format and an enormous deadline loomed for capital infrastructure spending. And as our panelists note, participation actually grew and diversified compared to traditional community engagement settings.

This webinar is the first of a three-part series focused on providing local leaders, developers, and advocates with tools and examples for staying in contact, sharing ideas, and getting interactive feedback to keep critical decisions moving forward. Stay tuned for our next webinar when we’ll take a deeper dive into the latest techniques and tools to conduct virtual community engagement.

A discussion recap

Holly Madil, Director of the National Charrette Institute (NCI), kicked off the webinar by welcoming participants, introducing speakers, and acknowledging the growing uncertainty brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. She described a growing interest in communities all across the world to continue engaging citizens and planning for the future as they adjust to virtual communication. Next, Bill Lennertz, founder of NCI and Principal of Collaborative Design + Innovation, explained how the NCI Charrette System works and the considerations that must be made to perform any element of it online.

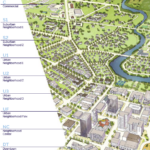

Tom Zavits, Senior Planner of Development Services in Missoula, gave an overview of his city—a booming city of 70,000 confined by a ring of rugged mountains—and the growing challenges of housing affordability. In an effort to accommodate its rapid growth, the city and county negotiated the master-planning of a 1,500-acre hayfield just west of the city limit known as the Mullan Area. After months of pre-engagement and education used to build community trust and inspire ownership over the future plans of a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood, the onslaught of COVID-19 meant re-inviting hundreds of stakeholders to participate in a new virtual format in just three days.

Participants then heard from DKP lead charrette manager, Jason King who described how the city prepared and structured the virtual charrette. Jason explained how the Virtual Charrette Hub was built and used to conduct focus group meetings, post work-in-progress design concepts, and solicit feedback. The process engaged nearly 300 stakeholders ranging from local engineers to environmental advocates, landowners to historic preservationists, technology-challenged seniors to small business owners and more. Jason wrapped up by sharing the exciting outcomes of the visioning process—a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood with high-quality multifamily housing, trails, community farms, and ecosystem regeneration.

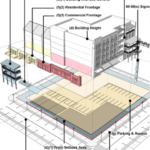

Next, DKP will translate the shared vision into a form-based code with clear development standards that will create compact and walkable neighborhoods with ample open space and a diverse range of housing choices. Further, the code is intended to “improve predictability in the outcome of future development within the Mullan Area by using a streamlined process of development application review and approval to expedite proposals that fulfill the purposes and intent.”

(Image: Jason King, DKP)

Questions?

We had so many great questions during the Q&A section of the webinar that we couldn’t get to all of them. We followed up with Tom and Jason to discuss answers to some of the questions we missed.

How did the fact that there was a partly-built out legacy traditional neighborhood development (TND) adjacent to this planning area inform your approach to the plan? Was it a helpful reference point for participants/community members?

JASON: Yes, there is a built TND area along Connery Way with commercial, a central green, and walkable block sizes. We did make reference to it in our films. Check out the film about retail. We also connected all the streets and green spaces of the surrounding development including that neighborhood.

The term walkable is abstract. Missoula’s walkscore is 46. Near the University of Montana – Missoula, it’s 58. How did the city define walkable?

TOM: I think the city defines “walkable” similar to most other cities. Missoulians predominantly use automobiles to get to employment and services although there is significant pressure (due to rising housing costs and limited land to build on) to create neighborhoods with enough density to support transit and local services and that don’t require the ownership of a car to get to work or services—which obviously is important in providing attainable housing. Missoula has a free transit service, a vanpool system, and is expanding its bike-ped trail system.

Were the concepts developed prior to the charrette?

JASON: All the work on the website was created during the charrette. As far as concepts, the county had a policy plan describing what it wanted to see; namely walkable urbanism and transit-oriented development (TOD). It was a foundational document. Visualizations and renderings were done on charrette by people who had only viewed the site through Google Earth. People like myself and our local partners have experience on the ground, which helped correct any inaccuracies in the renderings.

At what point in your plan making did you start the online charrette process? It seems like the city already had a lot of existing data to support the dialogue?

JASON: We started the online charrette process early. I believe we’d only had three or four meetings with stakeholders or members of the public prior to it. The county has a land use plan which described their walkable-urban & TOD aspirations generally. Our job was to engage the public and turn it into a specific plan.

TOM: We pivoted to a virtual format in just a few days. This was crucial for minimizing confusion and retaining participants who were previously involved. Originally scheduled meeting times were maintained so that participants did not have to reschedule—all they had to do was receive and execute the simple link instructions on a computer.

How many staff were involved in planning and executing the charrette?

JASON: The consultant team consisted of five people from Dover, Kohl & Partners, one member from IMEG, and one member of JACOBS engineering. That said, more Dover Kohl staff got involved as spectators or commentators because they were interested in the virtual charrette concept.

How does the budget of a virtual charrette compare to a traditional charrette?

JASON: A virtual charrette requires far less expenses for travel. More time is spent doing the work and less time is spent traveling or working out logistics. Videoconferencing, website, and filmmaking software is relatively inexpensive. In Missoula we had a set budget and we’re simply reallocating those funds to other tasks like detailed transportation modeling. Shall we estimate that virtual charrettes could foreseeably cost 25% to 40% less? I have conducted several virtual workshops and charrettes and that seems accurate. Remember that the charrette isn’t the entire project, however.

For context, The Mullan Neighborhoods project has a budget of $150K. In total it will consist of 12 months of consultant work. I imagine that some kind of virtual event could be done for any kind of budget.

How did participation compare to in-person engagement in Missoula? Did participants represent the demographics of the community as a whole? Who was left out?

JASON: I’m afraid that we can’t be exact about the socio-economic, geographic, or racial composition of participants, however the numbers of participants were far larger than an in-person, on-site event. We can see from website numbers that more Missoulians participated and they participated to a greater degree when it came to the time they spent reviewing and commenting on materials than even when it came to our downtown Missoula plan. It would appear that we had a range of ages and backgrounds. Anecdotally I observed a wide variety of participants. Our demographics are self-reporting, however. One big success was when I received comments from a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Their reservation is quite far from Missoula.

How many people had technical difficulties and accessibility concerns? How did you address this?

JASON: Internet access is fairly widespread in Missoula with over 92 percent of residents having monthly subscriptions. After receiving several calls and emails from people who were having problems with the platforms and meetings, we individually walked them through the process of signing into WebEx. Our team also made it clear that calling in was a viable option for those who didn’t feel comfortable using the video conferencing software. For participants who are vision-impared, we made sure that all content was read aloud in our films.

How did you facilitate stakeholder discussions and present technical information in an easy-to-understand format? Were participants able to collaborate amongst each other?

JASON: We had a 15 minute orientation presentation, 30 minute discussion with invited stakeholders and technical experts, and 15 minute public comment period. We did our best to avoid jargon and explain slowly and clearly, but ultimately, this plan is about streets, parks, and buildings of which people have vast personal experience.

Participants always joined moderated discussions. Certain groups also met on their own before attending our meetings. Still, the virtual charrette did not include a “chat room” or other tool. On some projects we have created discussion groups and provided a virtual room. We have also used tools like MindMixer which allows the public to “rank” each other’s ideas.

How did you ensure voting integrity, manage security, and avoid “Zoom bombing”?

JASON: We are able to monitor IP addresses, geographic locations, and histories (cookies) as people vote. The same computer can’t vote multiple times. That said, the voting is an unofficial gauge. We don’t treat the answers as if they are a statistically valid sample. To deal with security, we added a password, we didn’t share meeting links on social media, people only share the screen after getting permission, and we reserved the ability to mute participants.

What kind of software did you use to execute the charrette?

-Visual preference surveys: Google Forms

-3D modeling: Sketch Up and Lumion

-Website: Squarespace

-Video recording: Microsoft Powerpoint

Was the Missoula public appreciative and was the plan approved? What feedback did you receive from participants, especially from those who weren’t previously comfortable using the online format?

TOM: Our stakeholders were generally pleased with the switch to virtual means. I received only one negative comment which had to do with the timing of the charrettes and the COVID-19 emergency. Older Missoulians were also appreciative of the new process. They picked up on the new process quickly—only one older adult contact us ahead of time so they could practice using the virtual platform.

The Mullan Area Master Plan will go through the legislative approval process this fall.

Which aspects of doing the project virtually were more or less effective?

TOM: The ease or ability for someone who might have only participated in one in-person meeting because of traveling logistics, to participate or listen in on several meetings was appreciated by several participants I spoke with. Also, some participants I spoke with felt more comfortable speaking in a virtual setting, although I suspect there may have been others who felt less comfortable.

Great job explaining and clarifying. Everyone did a great job.

Great information – thanks