Fundamentals of Fenestration

How much of a building exterior is covered with openings, in particular windows and doors, how transparent the enclosing glass is, and how the openings are arranged are issues of fenestration. Not all form-based codes concern themselves with building fenestration. FBCs commonly regulate street width, block size, and buildings’ disposition on their lots and orientation to sidewalks—all issues affecting walkability. One can debate whether fenestration is also about walkability. It’s clearly more interesting to walk past buildings with windows and doors than ones without.

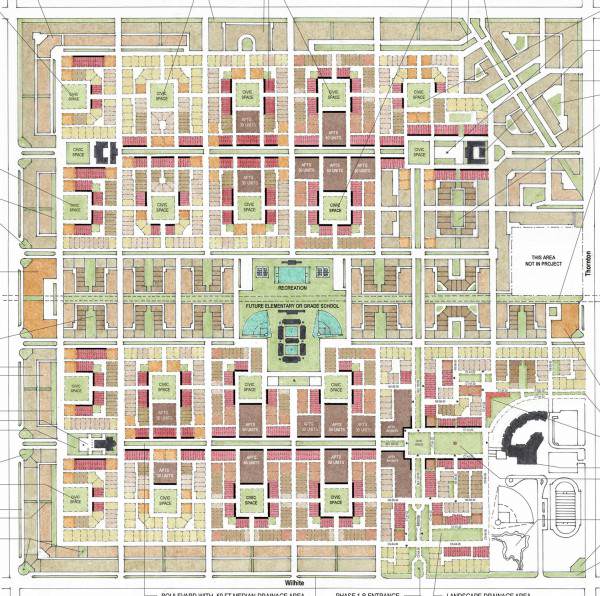

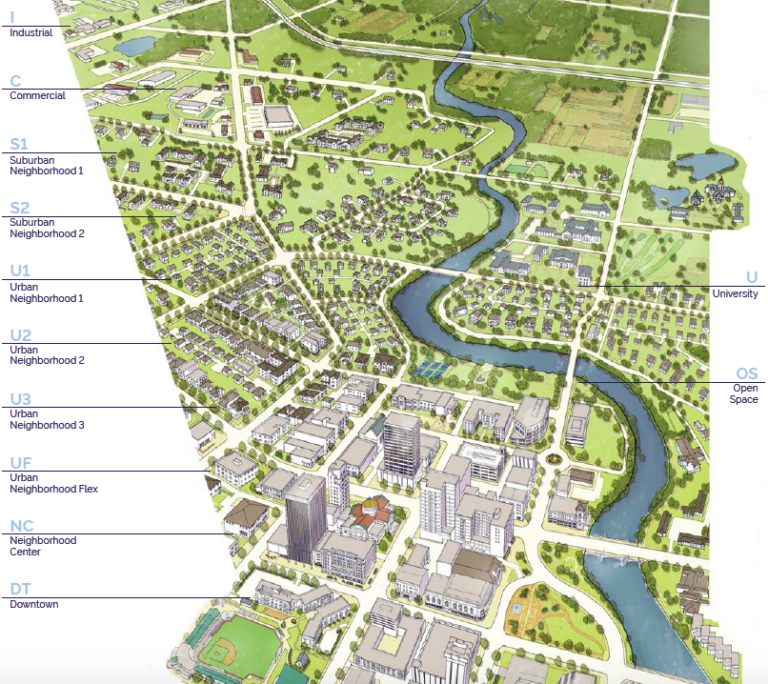

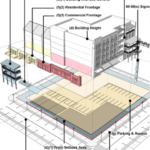

Just as important, fenestration influences the social character of public spaces. Fenestration affects how welcoming the building is and whether it participates with other buildings in creating a visually harmonized and immersive landscape. A neighborhood plan—a view from above showing the layout of streets, blocks, and building rooftops—leaves out this important thing that a form-based code can provide—what is the quantity and quality of the fenestration on buildings.

“A city is an ecological balance of things Public and things Private.

Fenestration is the portal between the two.”

– Geoff Ferrell

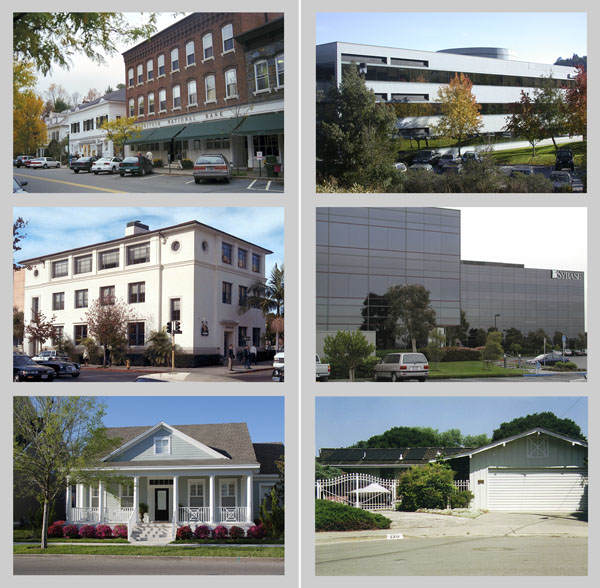

One of the most common arguments for windows from an urban design standpoint are that they provide eyes on the street and inhibit street crime—the important view is from inside to outside. But windows with reflective one-way glass can provide that. Views from outside to inside are also important. As eyes on a face are windows into the state of a person, windows as transparently glazed openings humanize a building by intimating the internal life of the structure. Compare this to tinted glass curtain walls or horizontal ribbon windows where it is hard to have any confidence that there are even rooms behind the glass. When the wall plane of a building is visually impenetrable and doesn’t appear to have openings, it affects not only the welcoming feel of the building, but also the social feel of the public spaces it faces.

On the buildings at the left, windows contribute a positive social tone. The visually impenetrable buildings on the right convey indifference to the public spaces they face.

The streets of Paris benefit from the unwritten fenestration standards of Baron Haussmann, the engineering prefect of Paris who oversaw the city’s redevelopment in the 19th century. He advocated a window aspect ratio and spacing that can be seen on most facades for the entire lengths of many of Paris’ iconic streets. The effect is to create urban spaces visually tied together throughout. His design dictums had the enforcement weight of Emperor Napoléon III behind them. In our time it is difficult to get a Parisian degree of design conformity from building to building. Nevertheless, some degree of pattern consistency from building to building harmonizes place identity.

The example of Paris demonstrates the influence of fenestration standards on the experience of urban spaces. Parisian street walls are harmonized by consistent sizes and spacing of windows from building to building.

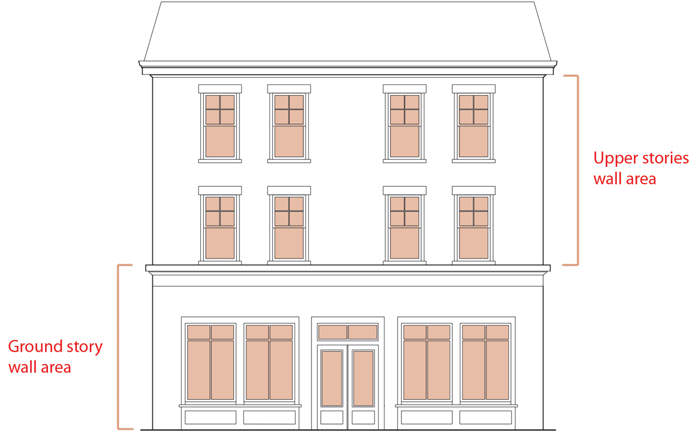

A fenestration element in a form-based code typically describes the required amount of window and door area as a percentage of the wall—for example 30 to 90 percent of a commercial ground floor facade, and 20 to 70 percent of the upper story facade. This range may vary depending on the urban context. When calculating the opening area of a door or window, many form-based coders exclude non-transparent parts such as lintels, frames, sills, and mullions, but include window parts such as muntins if they are less than an inch wide. Historically fenestration didn’t take up a large percentage of walls. In the example facade below, the upper fenestration comprises 19% and the lower fenestration 26% of their respective wall areas.