Leading from in Front and from Behind: Opticos Design Uses a Grassroots Approach to Improve Urban Planning

“When listeners become leaders, the world changes.” –Rev. Kellen Roggenbuck

Traditionally, U.S. cities and towns are planned and designed by urban planners, architects and local government officials without much input from future or even current residents. The approach is a prescriptive one that is designed to regulate — and at its worst, dictate — where people live and work; it does nothing to accommodate residents’ priorities and preferred lifestyles. Many people have little or no say over where or how far they will travel from home to reach work, shopping or entertainment, or what these various settings will look like or offer. We can look for a community that meets some of our professional and personal expectations, but we rarely are given the chance to help make one.

Berkeley, Calif.-based Opticos Design wants that to change and has been working since it was founded in 2000 to make it happen. The firm does this, in part, by helping local governments and residents develop form-based codes that encourage and result in appealing, walkable neighborhoods that serve residents in many different ways and provide easy access to various types of transportation.

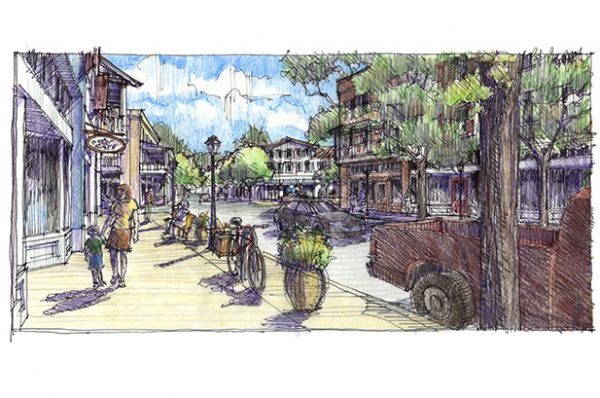

“Form-based codes have the ability to deliver proximity to retail and services, and they often generate an interesting public realm that realistically connects daily destinations,” said Tony Perez, Opticos’ director of form-based coding. “Because of a form-based code’s ability to see all the components and uses in an environment, regulations can be selected and applied to generate the physical conditions that promote walkability.”

Notably, Opticos principals Dan and Karen Parolek helped to write the first comprehensive book on form-based codes and co-founded FBCI to further develop them and promote their use.

When helping a community to better serve its residents, the firm also makes a point of soliciting input on the planning process by inviting them to participate in multi-day, open-door charrettes during which they can share ideas and expectations, make recommendations and even help test proposed codes.

Dan Parolek believes this broadly inclusive approach to urban planning and design is essential because residents can identify a city’s strengths, weaknesses and potential improvements better than any outsider. “We’re working in other people’s hometowns. We don’t live in these places, they do,” he observed.

Although small, Opticos has made a major impact in many diverse locations, extending from Austin, Texas, to Kauai, Hawaii, and even as far as Gabon, Africa, and the firm makes a point customizing the form-based codes it helps to write to meet each community’s unique needs.

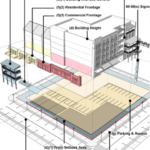

In Cincinnati, for example, Opticos helped the city develop a form-based code that could be applied in an incremental way, allowing neighborhoods to adopt place-specific codes rather than adhering to a single, citywide code. This approach allows a code to grow organically across Cincinnati and encourages neighborhood-based planning, quality urban infill, and the retrofit and improvement of existing buildings and neighborhood fabric. The code establishes transect zones and specifies standards for each transect building and frontage types, walkable neighborhoods, and thoroughfares. Additional standard sections apply to hillside and historic districts, parking, and corner stores. One of the code’s most notable contributions is its walkable neighborhood standards, which apply across transects and specify the allocation of transect zones, pedestrian sheds, neighborhood centers, thoroughfare connectivity, open space and civic space standards. The code also is expected to accelerate development by streamlining the city’s permit and approval process.

An example of the new code in action is a mixed-use development project that will be built in Cincinnati’s College Hill neighborhood. Affordable housing and retail shops will be built in the heart of the neighborhood’s business district.

This form-based code won the Grand Prize for Best Planning Tool or Process at the Congress for the New Urbanism’s Annual Charter Awards in 2014 and a Driehaus Form-Based Codes Award honorable mention.

Opticos also created the Missing Middle Housing concept, which accommodates a range of multi-unit or clustered housing types — such as duplexes, fourplexes, and bungalow courts — that are compatible and in scale with single-family homes. The variety of housing types attracts residents from many different backgrounds and walks of life, which can increase a community’s vibrancy and resilience.

“Missing Middle Housing is highly sought after — especially by millennials and empty-nester baby boomers, today’s two biggest demographic groups. … Smaller households tend to eat out more, helping our neighborhood attract wonderful restaurants. Diverse households keep diverse hours meaning we have more people out walking our streets at more varied hours — keeping them safer,” said Ellen Dunham Jones, professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and coauthor of Retrofitting Suburbia, Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs.

Form-based codes and Missing Middle Housing are closely related, as effective form-based codes can often assist in “finding” or enabling Missing Middle Housing, Parolek explained. “Form-based codes introduce often ‘missing’ zoning districts with new zones that encourage house-scale, multi-unit buildings or a cluster of buildings — like a cottage courts — with higher densities, and form-based codes really level the playing field for small units by not relying on density as the operating system,” he said. “Instead, form-based codes reinforce building types as the ingredients of a neighborhood ‘recipe,’ through which you can directly allow a range of building types within each new form-based zone/transect zone.”

Missing Middle Housing provides enough people to support locally serving commercial and retail amenities and make a community transit-supportive,” Parolek added. “Also, it provides diverse housing choices, thus promoting an economically diverse neighborhood. From an economic development standpoint, there is a huge unmet demand for this type of housing in every part of the country. Cities that enable these types are going to prosper economically as more people choose to move to these communities because they are providing these choices. Companies and jobs will follow.”

Opticos makes a point of practicing what it preaches both professionally and at a personal level. In 2007, the firm became one of the first B Corporations, which refers to companies that have been certified by the nonprofit B Lab, to meet rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency. The certification helps Opticos to obtain support in adopting socially, environmentally and fiscally responsible practices, while serving as a successful business model to other firms that share these goals. In 2012, the firm took another step to advance its commitment to social and professional responsibility by becoming one of 12 initial California Benefit Corporations, a revolutionary new type of business that integrates environmental, social and fiscal responsibility into decision making. These principles affect every project Opticos takes on and are reflected in employees’ lifestyles. Staff members often cycle, walk or take public transit to the firm’s office, which is located in a mixed-use urban center.