Webinar recap: Using an NCI charrette to create a vision for a form-based code

This November, we hosted “From vision to implementation: Using an NCI charrette to create a vision for a form-based code,” a joint webinar between the Form-Based Codes Institute and the National Charrette Institute. Speakers shared their experiences using NCI charrette workshops to develop form-based codes in Norman, OK and Arlington County, VA.

Click HERE to access the full webinar recording.

Form-based codes are designed to bring a shared community vision to life. These zoning codes translate desires of the public—town homes there, street trees along here, and taller buildings over there—into straightforward standards that regulate future development. But creating a mutually supportive vision of how a community looks and aspires to grow takes time.

The National Charrette Institute (NCI), which is housed at Michigan State University, has developed a charrette process that helps communities build capacity and collaboration to develop a shared vision quickly and effectively.

A discussion recap

Holly Madill, Director of NCI, kicked off the webinar by explaining how the NCI Charrette System ultimately brings together residents, decision-makers, and content experts during an uninterrupted work session to design solutions for difficult community issues. As she noted, Preparation is key to ensure the charrette is as inclusive and multidisciplinary as possible. And the charrette process might not be right for every community—it works best where solutions to complex design problems are pressed for time with impending development, when the stakes are high, and where tricky politics and low-trust environments coincide. It’s particularly helpful for communities taking on a form-based coding process where stakeholders can learn about the project and help code writers inject a community vision into development standards.

The webinar then turned to code writers and charrette managers who described how NCI charrettes aided in the development of form-based codes in Norman, OK and Arlington County, VA.

Bill Lennertz of Collaborative Design + Innovation introduced a project for a neighborhood that sits between the University of Oklahoma and downtown core of Norman, OK. Tensions between community members, city leadership, and the university had simmered for years over housing. Mid-rise apartment buildings that had been previously proposed were opposed by long-standing homeowners but it was clear the area needed a way to fill the housing gap between larger apartment buildings downtown and single-family homes.

The project team pulled together residents, planning staff, and university leadership during a pre-charrette event to better understand the local context, people, and eventually rebuild trust. Over two days and 75 interviews, the team established relationships with stakeholders and developed a clear understanding of the community’s concerns, its strongest assets, and places outside the city that residents admire—aspirations of what Norman could become.

Bill then described the activities of the five-day Center City Vision Charrette: hands-on exercises and opportunities for residents to draw their ideas; technical meetings with transportation, building code, land use, and legal staff; public meetings; and abundant open-studio time for community members to observe the designers at work.

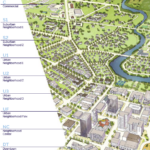

Sixty-eight percent of charrette participants agreed that this was an appropriate way for Campus Corner to evolve. (Image: Opticos Design)

Mary Madden of urban design and town planning firm Ferrell-Madden then discussed how the team drafted a form-based code to best retain and implement the community vision. They determined which areas were right to maintain, revitalize, or fully transform and identified what new development standards would be needed to enable the character residents desired.

“We reminded people why we were going through this process and why they needed to think about it differently … and the really big idea was to help people think about placemaking—not land use, FAR, or dwelling units per acre.”—Mary Madden

The form-based code was adopted, but not until three years post-charrette. And this, Mary explained, was a pitfall of the project—it’s absolutely crucial to minimize the time lapse between charrette, code drafting, and code adoption. A lag in the Norman project meant dealing with a change of city leadership, citizens losing familiarity with the project, and ultimately a “watered down” form-based code.

But progress is evident in Norman and much of the community’s aspirations are shining through new development. Missing middle housing types—particularly duplexes and town homes—are sprouting up in a way that improves placemaking and walkability in the neighborhood while supporting new renters, homeowners, and college students.

Chris Zimmerman, vice president for Economic Development at Smart Growth America and former member of the Arlington County Board, introduced the case study for Columbia Pike—an initiative to transform a suburban-style commercial corridor into a better place for its residents and businesses. Visionaries of the project not only sought a form-based code, but a comprehensive strategy to preserve the region’s largest repository of affordable housing, elevate historic preservation, and promote future development supportive of its extremely diverse population.

Inta Malis, former chair of the Arlington County Planning Commission, illustrated the long history of debating Columbia Pike’s destiny—reaching as far back as 1945—and years of failing to kick-start any quality reinvestment. In the nineties, a revitalization association brought together neighborhood advocates to begin strategic conversations about a path forward.

In 2002 and after 149 meetings, the project team held the first charrette focused on mixed-use nodes along the corridor—leading to the development of the Columbia Pike Commercial Centers Form-Based Code. A second charrette took place nine years later to hone in on the Pike’s neighborhoods. Amy Groves of town planning firm Dover, Kohl & Partners explained that much like the Norman project, the Arlington County initiative included three phases: a public kick-off event to gather input through interactive exercises, an on-site idea-testing studio, and a final presentation to review the week’s worth of work. But again, this was only the pinnacle of the process after weeks of careful preparation.

In 2002 and after 149 meetings, the project team held the first charrette focused on mixed-use nodes along the corridor—leading to the development of the Columbia Pike Commercial Centers Form-Based Code. A second charrette took place nine years later to hone in on the Pike’s neighborhoods. Amy Groves of town planning firm Dover, Kohl & Partners explained that much like the Norman project, the Arlington County initiative included three phases: a public kick-off event to gather input through interactive exercises, an on-site idea-testing studio, and a final presentation to review the week’s worth of work. But again, this was only the pinnacle of the process after weeks of careful preparation.

A considerable amount of the pre-charrette work was dedicated to pressing concerns about affordable housing. The project team hosted professionals from around the country to present their approaches to the complex issue and ran through scenarios for renovation, infill, and complete redevelopment of existing affordable housing complexes along the Pike.

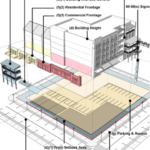

Following both charrettes, code writers translated the resulting community vision into a form-based code regulating plan, which keyed specific building envelope standards—height, siting, and function of structures—to different parcels along the corridor. And between the charrettes, project consultants and citizens refined strategies for making Columbia Pike more walkable and multimodal during a phase of street space planning. This resulted in regulations for streetscape elements like sidewalk furniture and street trees and dimensions for travel lanes, bike lanes, and sidewalks. In the end, Arlington County adopted two form-based codes (one for commercial nodes in 2003 and one for adjacent neighborhoods in 2013) and an integrated affordable housing strategy. Together, this multi-pronged approach has made for a net-zero loss of affordable housing, financing and planning incentives to spur development, and requirements for new projects to include affordable units on-site.

In the end, Arlington County adopted two form-based codes (one for commercial nodes in 2003 and one for adjacent neighborhoods in 2013) and an integrated affordable housing strategy. Together, this multi-pronged approach has made for a net-zero loss of affordable housing, financing and planning incentives to spur development, and requirements for new projects to include affordable units on-site.

Lessons learned from the Columbia Pike project echoed those from Norman—especially the damage delays have on trust, motivation, and buy-in developed during the charrette. Meanwhile, it’s important to increase understanding of key issues—through stakeholder meetings and analyses—and maximize publicity before deciding the community is “charrette ready.” There’s also a need to balance passionate feedback from citizen designers with technical recommendations from local planning experts required to address complex market realities.

“It really works! Already we have building projects going up that are consistent with the code, that are bringing new opportunities, more walkable environments, and more housing of all kinds for the people of our community.”—Chris Zimmerman

Questions?

We had so many great questions during the Q&A section of the webinar that we couldn’t get to all of them. Here’s what our speakers had to say about the ones we missed.

How can we respond to skeptical community members who question the legality of form-based codes? Does the regulating plan have the same status as a zoning map for a particular area?

Mary: The legality of form-based codes (FBCs) has not been challenged in court; FBCs regulate the same basic health, safety, and welfare standards as conventional zoning, simply with different priorities or hierarchy. In some states, some regulatory aspects may be limited. For example, in some states, architectural details such as exterior building materials and fenestration proportions cannot be regulated via zoning outside of a designated historic district; in some other states, municipal design standards for detached single-family housing have recently been prohibited. As with all zoning, it is important to know what the state enabling legislation permits or prohibits. (The few legal challenges of which we are aware have been related to process, rather than regulatory, issues.) If the FBC is mandatory, the regulating plan is typically adopted as the location-specific zoning map; if it is optional, it may be adopted as an overlay on the existing zoning map. Most regulating plans include more information than is typically found on the zoning map.

If a proposed form-based code addresses factors that are typically included in subdivision regulations as well as zoning codes, how do the form-based regulations situate themselves relative to both of these ordinances. In other words, can a form-based code regulate factors across existing but separate ordinances?

Mary: Again, this depends on the state law—if Unified Development Ordinances (UDOs) are permitted, then the form-based regulations that are typically found in subdivision can simply be included in a new form-based district (most commonly maximum block lengths, connectivity requirements, sidewalk standards, etc.) If the zoning and subdivision can’t be consolidated, the issues can still be addressed, typically with a combination of cross-references in the zoning ordinance and new language in the subdivision regulations, that establishes new standards and/or identifies those regulations that simply do not apply in form districts.

What would a small community (approximately 5000 year-round, 20,000 during the summer) expect to spend on a charrette process?

Holly/Mary/Bill/Amy: While we wish that there was an easy answer, each community and issue are so unique that a one-size fits all formula generally doesn’t work very well. The budget for a charrette is less dependent on population size than on the complexity of the project, the geographic size, and type of deliverables desired. More complex projects or projects spanning large geographies tend to cost more than simpler ones. For example, if the climate is very contentious, the issue is complex, and/or there are lots of viewpoints, the cost will likely be greater because there is more preparation required to get the people or data part of the charrette ready.

It’s common to spend 50% of the entire charrette project (preparation, charrette, implementation) on the preparation phase to ensure the success of the multi-day charrette. The charrette itself is typically one third or more of the total project budget, which also depends on the specialists (transportation engineers, economists, etc.) needed to create the products and whether they are municipal staff or consultants. Deliverables vary significantly—from a high-level vision plan and charrette report to a detailed vision plan with numerous illustrations and renderings, economic and traffic analysis, short, medium, and long-term action items, and a form-based code. Or the outcome may be limited to policy recommendations. The charrette/code writing team’s level of involvement post-charrette and initial code drafting (i.e. will team members be involved until code adoption?) also contributes significant cost.

For reference, the total cost of the Norman project (for a defined geographic area/district within the city), charrette preparation, charrette, and the writing of the form-based codes was $200,000. More accurately, the budget should have been $225,000 given the extended post-charrette code writing period.

In Arlington, what was the effect of the killing of the light rail initiative on the plan and the form-based code?

Amy/Chris: The Columbia Pike initiative was not dependent on BRT or light rail for success, but instead seen as an opportunity to grow ridership and capacity of what was already highly-used bus service. The charrette and planning were not specific on future investments in transit because the area was already densely populated—so it was more akin to “development-oriented transit.” We also didn’t need a shiny new streetcar to initiate redevelopment because we were looking for just enough property value appreciation to preserve the affordable housing that was already there.

Was parking management a sticking point?

Mary: Parking supply and demand can become a sticking point, and did somewhat in Norman (due to the destination environment of Campus Corner, the limited existing supply of a publicly-accessible parking, and the time required to form a public-private partnership to site and develop a parking structure). However, the drafting of a form-based code can provide an opportunity to review and revise a community’s approach to parking management, particularly the quantity and location requirements; reducing (if not removing) minimums, and permitting shared and off-site parking are great places to start.

Did organizers get low income and minority communities to participate over the long time span of the various meetings and charrettes?

Mary: The study area in Norman did not have a significant minority population to reach out to. The economic demographics of the resident population was skewed by the students, but were primarily lower-middle to middle income. There were a large number of renters, who were hard to identify and engage in the process; although several did participate in public events. The property owners (both commercial and homeowners) participated throughout the process; the landlords were less engaged until the draft form-based code was released.

Amy: For the Neighborhoods Plan, there was a concentrated outreach effort to encourage participation by a broad spectrum of the community, which included bi-lingual promotional materials, and posting those materials where they were most likely to be seen (for example, signs on buses, posters in rental apartment buildings, sending flyers home with school students). We also had numerous stakeholder interviews that included property and business owners as well as neighborhood representatives.

Do communities that enact form-based codes tend to see quantifiable benefits for local markets (i.e. percent vacancy, property valuation, new investment, etc.)?

Chris: Yes, we believe this is the case. By facilitating development that wouldn’t otherwise happen, and by shaping it in a way that positively impacts neighbors, form-based codes create a built environment that enhances the local market. Regardless of being a coffee shop, grocery store, or bank, all new businesses contribute to the well-being of existing residents and businesses, both in terms of placemaking and commerce. The heightened predictability that comes with form-based codes also lowers the risk of new development because you know the exact form of subsequent projects thanks to transparent and prescriptive building envelope standards.

What specific strategies have you implemented at Columbia Pike to keep real estate values from becoming unaffordable?

Amy/Chris: The form-based code includes a requirement for on-site affordable units in proportion to any new density and the accompanying Columbia Pike Neighborhoods Plan area plan includes incentives for affordable housing. The specifics can be reviewed in the code and plan.

The code requires 20–30 percent of net new units to remain affordable for 30 years to households earning up to 60 percent of the area median income. Ideally these units are included on-site, but if they are off-site, the developer has to build more affordable units the further away they are placed. Alternatively, the developer can pay into a county affordable housing fund. Developers can also achieve up to six bonus stories for projects that provide on-site affordable units beyond this minimum requirement.

Another tool—transfer of development rights (TDR)—allows developers to move density from places of preservation (i.e. conservation areas) to certain revitalization areas. There’s also a transit-oriented affordable housing (TOAH) fund to help affordable housing developers reduce their project costs. It’s specifically aimed at developers who are applying for Low Income Housing Tax Credits and allows them to put TOAH funds toward infrastructure-related items like underground utilities, tree preservation, and streetscaping.

Top: A resident of Norman, OK presents during the Center City Vision Charrette. (Image: NCI)