Practical Idealism: FBCs as the Framework for Building Sustainable Places

[wds id=”1″]

Great cities, towns and neighborhoods do not develop by trial and error. Rather, their growth is guided by the community vision of those who live and work there.

This view underlies the work of Geoff Ferrell and Mary Madden, principals of the Washington, D.C.-based urban design and town planning firm Ferrell Madden, who conduct urban planning and write form-based codes (FBC) for communities throughout the United States.

The firm follows a two-pronged approach to helping make communities more economically, environmentally and socially sustainable. First, they work with the community to define or clarify its overarching vision, which serves as the road map for the project. Then Ferrell and Madden “ground-truth” the project area in terms of physical, political and market realities to ensure the vision can be achieved. The most visionary plans and innovative development codes remain unimplemented if the local economy does not support them. A well-crafted form-based code should work with the market, providing the framework for both public investment and private sector development to fulfill the community vision over time.

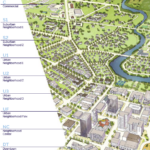

As an example, working with Coral Gables, Fla.-based Dover-Kohl & Partners in 2002, Ferrell Madden wrote the form-based code for the Columbia Pike Corridor in Arlington County, Va. The county expressed its desire to see the busy 3.5-mile suburban thoroughfare transformed into a pedestrian-friendly, traditional main street with access to public transportation. The pike, which had seen little development over the previous 30 years, was lined with suburban development, ranging from strip shopping centers to mid-20th century garden apartments — from auto dealerships to high-rise condominiums and fast food establishments — all backing up to single-family neighborhoods.

“Columbia Pike was a typical aging, auto-oriented corridor,” said Ferrell. “It was a linear gray-field of asphalt parking lots and strip commercial development. The corridor was zoned for far more retail space than it could support.”

The consulting team held a public design charrette and met with a full range of stakeholders, including elected officials and planning commissioners; county staff from public works, planning, and economic development; property owners; neighborhood associations; local developers; the pike’s nonprofit redevelopment organization; as well as with the regional transit authority and Virginia’s transportation department. They drew on the input provided by these individuals and groups to define the community vision and develop a form-based code.

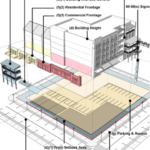

The county adopted the Columbia Pike Form-Based Code in 2003 to transform four commercial nodes into mixed-use centers. The code requires three- to six-story mixed-use urban buildings, fronting on the pike, and wide sidewalks, street trees and on-street parking. Development on the back of each block, facing the existing neighborhood, was mandated to step down in scale and be of a consistent character and use. The plan and code laid out new streets to complete the traditional grid, improving walkability and connections to the adjacent neighborhoods. They also specified locations to establish new public squares. The code encourages “park-once-then-walk” behavior within each center through its emphasis on the public realm along with the removal of on-site parking requirements and the creation of a parking management strategy.

Virginia is a strong property-rights state, and the county avoided some legal and political issues by keeping the “by-right” zoning in place and overlaying the FBC as an option. Developers can choose to use either the conventional zoning or the form-based code for proposed projects, although effectively, few projects “pencil out” if the conventional code is used. As a result, since the FBC was adopted for the centers in 2003, it has fostered the construction of 10 mixed-use development projects, including more than 1,500 homes, more than 280,000 square feet of retail and office space, a new community center and a new public plaza. The transformation envisioned by the community is well underway.

“The fact that the code has continued to work well for Columbia Pike over more than a decade, even as the economy has gone through a major recession, shows that the vision was realistic and the FBC provided a sound framework for private reinvestment.” said Madden.

In 2013, the county asked the consultants to revisit the Pike project to prepare a master plan and FBC for the residential areas between the mixed-use centers, which are dominated by large apartment complexes, to encourage compact, walkable infill and redevelopment, while maintaining historic buildings and existing affordable housing.

The “neighborhoods” code is expected to guide redevelopment over the next 30 years and the addition of 9,500 homes along the corridor, the county said in a press release describing the code. The county chose to use transfer of development rights and green building standards in conjunction with the FBC to achieve public policy goals relating to historic preservation, affordable housing, and environmental sustainability.

Ferrell Madden has worked on a variety of projects, each with its own challenges, both independently and as part of a larger consulting team. But a consistent emphasis in their work is the drafting of form-based codes that reconcile the community vision with the local context and the real world economy. In Portsmouth, Va., where municipal expansion is constrained by the waterfront and bordering municipalities, growth opportunities consist of infill. The firm led an effort to design a code that shaped redevelopment to create an urban neighborhood to complement the adjacent historic downtown and allow for the future introduction of a light rail line.

The firm also helped the Dallas-bedroom community of Farmer’s Branch plan the redevelopment of an underused industrial district in anticipation of the extension of the Dallas Area Rapid Transit light rail line. The FBC developed for Farmer’s Branch was designed to transform a landscape of parking lots and aging strip malls into a transit-oriented downtown of street-level shopfronts, sidewalk cafes, and other commercial establishments along broad, tree-shaded sidewalks, with mixed office and residential space in the buildings’ upper stories. The code also includes architectural standards that address building materials and other details.

In Peoria, Ill., Ferrell Madden led an interdisciplinary team that included architects, economic consultants, zoning experts and renderers from across the United States to conduct an urban design charrette and draft form-based districts to guide the redevelopment and revitalization of three neighborhood “main streets” and a large historic warehouse district on the Illinois River, all within the pre-World-War II core of the city. In all cases, the Peoria form-districts emphasized the creation of walkable neighborhood centers integrated with adjacent neighborhoods.

One challenge code writers frequently face is the tendency of people to misunderstand what an FBC is, what it can accomplish and the prevailing need for a clear but realistic vision to guide code development.

“Many communities hire a firm to write a form-based code because they want more mixed-use development or to rehabilitate an aging corridor but refuse to introduce the more flexible zoning requirements that are needed to get them there,” Ferrell explained. “FBCs are intended not just to expand the number of activities or types of land uses that can be conducted within a certain amount of space, but also to create a sense of place. It matters, not just what buildings you construct but the type of environment and atmosphere that they form together.

“Areas that communities expect to remain auto-oriented aren’t the best candidates for a FBC; it’s better to focus the energy where it can create a sense of place, with a form-based code to shape the buildings that will form the environment,” he added.

The partners said they are interested in expanding the knowledge about FBCs by firms and municipalities that are unfamiliar with them by partnering or peer review activities.

“FBCs can be the linchpin for communities that want to address sustainability, public health and economic vitality through the development of more compact, walkable places,” said Madden. “We are proud of our contribution to that effort.”

1 Reply

Trackback • Comments RSS

Sites That Link to this Post