Market-Responsive Form-Based Codes

Originally published in Better! Cities & Towns, April-May 2013.

Richardson, Texas, an affluent inner-ring suburb of Dallas, and home to many telecommunications corporations, wants to remain attractive to employers in coming decades.

Key to that goal is becoming more walkable and connected to transit, qualities that many of today’s young and talented professionals are seeking. There are five Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) stations in Richardson, and unfortunately not one is in a walkable neighborhood. Such areas are in short supply in Richardson, which grew up entirely after World War II.

But a 100-acre previously undeveloped parcel adjacent to one of the stations will establish a new pattern: The site was rezoned recently for 3,200 residential units and up to 6,000 jobs. State Farm Insurance Company, which could have located anywhere in the region but was looking for a walkable urban center, chose this site.

As long as builders adhere to a new form-based code (FBC), no further public hearings are required. “We eliminated the risk of NIMBYism for a theoretical maximum buildout within a wide range of uses,” says Scott Polikov of Vialta Group, LLC, A Gateway Planning Company. “There’s nothing more market-responsive than that.”

A February report by real estate consultant Robert Charles Lesser & Co. (RCLCo), called “Market Pitfalls of Form-Based or Smart Codes,” criticized some FBCs for market inflexibility. Although the report cited no specific codes — and so was difficult to refute —it stung some new urban practitioners who take market demand seriously.

Developers who wanted to reduce political and business risk initiated the code for the Bush Central TOD, as the Richardson site is called. The city gained assurances that the public realm would be built out in a way that is walkable and mixed-use, while the developers got flexibility and “by-right” entitlements, Polikov says. The master developersBush/75 Partners sold all the land, at a premium, within a year and vertical construction is underway at a rapid pace. Zale Corson Group is developing an urban multifamily project designed by JHP Architects, and KDC Development Company has purchased the remaining land for a mixed use, live-work-play project.

“We made the argument that this kind of development is required to keep attracting corporate citizens,” he says. “They wouldn’t be able to bring in the cool, echo-boomer development without a form-based code.”

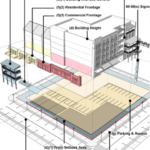

City entitlements allowed higher densities without micromanaging uses, he adds. Within the 18 urban blocks that make up the site, uses are mostly flexible. On some streets, buildings must have first floors that accommodate retail — but other uses can occupy these areas if the market for retail lags.

“The form-based code allowed us to get a richer building envelope and enabled development to evolve over time,” Polikov says. “That’s a big story that the RCLCo criticism misses.”

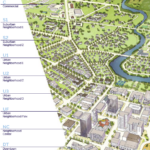

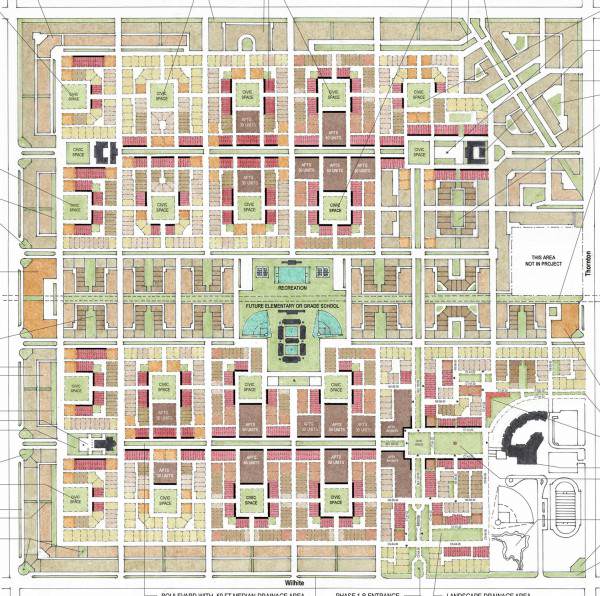

The Bush Central TOD — named after a nearby highway that is named after the first President Bush — is laid out on a simple grid to be built out intensely. Public spaces are plentiful and a large natural park with trails along a creek will provide a connection to nature. The project will create a regionally significant urban center for the north side of Dallas.

Trinity Lakes

Across the metro area on the East Side of Fort Worth — a far less affluent part of the region — a form-based code was approved in December 2012 for a 175-acre transit-oriented development called Trinity Lakes.

This project is in the middle of suburban sprawl with a diverse Latino/white/African-American population. An existing commuter rail line between Dallas and Fort Worth borders the site, but a station needs to be built. A high-speed thoroughfare, Trinity Boulevard, bisects the site and must be transformed into a complete street.

Trinity Boulevard in East Fort Worth is currently a highway but will serve as a town center. Rendering courtesy of Vialta Group, LLC, A Gateway Planning Company

The city, having adopted a FBC for an area adjacent to downtown, has experience with this type of regulation. The Trinity Lakes FBC was the first proposed by a private developer in Fort Worth. Residents of a large adjacent development, who have nothing but commercial strip retail nearby, were all for it. “They are sick of driving out of East Fort Worth for amenities that other neighborhoods have,” Polikov says.

Fort Worth is an area that gets a lot of development: In 2013, more than 4,000 residential building permits were issued in the city, about a third of them for multifamily units. But nothing like this has been attempted outside of the downtown core, let alone in a working-class neighborhood.

The city agreed to tax-increment financing (TIF) for $75 million in infrastructure to build the rail station, convert the highway into a multiuse boulevard, and pay for street, stormwater, and other improvements. The city and county will get a portion of new taxes for 20 years and then 100 percent thereafter.

The site links into the Trinity River Trail system in addition to the regional rail network.

The FBC is similar to the Richardson project. As long as the form-based aspects are adhered to, the developer has by-right entitlement to build out the project. “Form-based coding provided the vocabulary to communicate the benefits to neighbors, and it was the analytical vehicle to estimate a much higher tax-base capture,” Polikov says. Planned development in Trinity Lakes is estimated at $750 million, and it could transform this part of East Fort Worth.

High desert Savannah

Affluent or working class, the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area is a fast-growing region with 6.5 million people, and what works there may not work in other parts of the US. Clovis, New Mexico, with a population of 37,000 and located 90 miles from Lubbock, Texas, the nearest city of any size, could not be more different. Yet a market-based FBC could work there as well, Polikov says.

Cannon Air Force Base, a big part of the town’s economy, is expanding with a special operations command headquarters. Many officers and enlisted personnel have lived in Europe or big cities. A 640-acre project by local developers Jeff Watson and Sid Strebeck is designed to create the kind of environment that would appeal to the service men and women.

The project takes up an entire square mile section north of town, and the first neighborhood will be anchored by a middle school and park for which the developers are donating the land.

Saddlewood in Clovis, New Mexico, takes inspiration from Savannah, Georgia. Plan courtesy of Vialta Group, LLC, A Gateway Planning Company

Saddlewood is designed around 20 squares, much like Savannah, Georgia, and each square will be a module for development that includes a full range of housing types. The housing surrounding each square is, in effect, a phase of development that allows market flexibility, Polikov says. “We looked at historical places that allow variety but replication and we were influenced by Savannah,” he says. “There’s a predictable amount of infrastructure investment and we can build as much as we need,” he says.