Finding The Right Path Through Design Review

Originally published: May-June 2014 in Better! Cities & Towns

Municipalities—searching for ways to better shape development — must tailor their approach to the community’s size and professional resources.

Formulaic buildings and generic places are a particularly American blight. They have eroded the physical character of many cities and towns. In some communities, they have spoiled the appetite for growth and development.

What’s to be done? Municipalities increasingly recognize the downside of bad development. but many struggle to come up with a better alternative.

Will more regulations and reviews deliver the distinctive, vibrant places that communities want? Not necessarily. We are surrounded by places that are highly regulated yet badly planned and poorly designed.

Crude regulations and protracted review processes can make walkable places difficult to build. Too often, the local zoning code and development review process lean heavily toward reducing the negative effects of land uses, while offering little direction that enhances the quality and character of development.

Many cities lack an institutionalized design review process. Applicants and their design teams frequently are outraged by the vagaries of untrained planning commissions or political interference from elected officials. “Designing from the dais” seldom results in good design.

To steer municipalities toward a more productive approach, in this article I discuss the potency of design review, the varied people involved in the process, and different options and formats that can be used.

When and how to use design review

Every development has the potential to preserve and enhance its built and natural environment, stimulate the economy, and improve the quality of public life. Design review can be an efficient, cost-effective way to improve the spatial and functional quality of buildings and of spaces—largely shaped by buildings—that give character to a place.

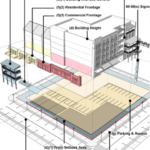

A typical design review focuses on site and building design issues. In historic districts the design review may include more detailed regulations and/or a set of discretionary elements that control scale and massing, materials and detailing, roof forms, and openings.

In recent years, new urbanists have in many cases used form-based codes to provide direction about the intended character of a place. These codes provide clearer, more specific guidance, quicker approvals, and more predictable results than had been available through conventional zoning codes. However, even the most prescriptive form-based code cannot eliminate the exercise of judgment.

The Urban Design Peer Review Panel in Dallas reviewing a mixed use development

proposal located in one of Dallas’ eighteen Tax Increment Financing districts.

Photo Credit: Dallas CityDesign Studio.

That’s where design review comes in. The design review process allows cities to ensure compliance, use informed judgment on the aesthetic aspects of a proposal, consider creative interpretations, and respond to nuances and dynamic conditions found within an area. Design review offers early feedback and observations that could lead to an enhanced scheme. It also strengthens the spine of decision makers to say no to poorly designed schemes, while supporting innovative and high-quality designs.

Timing matters: Design review is most effective when it’s integrated into the early stages of the development review process. It is both easier and more cost-effective to make changes when the development is not too far along.

Ventura, California, offers a conceptual review process to provide early direction on concept sketches, before an applicant develops a complete set of drawings for final approval. A conceptual review reduces risk and expense by exposing weaknesses and providing direction early in the process.

The players

Design criticism is a delicate matter that is best received from professional peers possessing recognized expertise. In bigger cities, reviews are conducted by a committee of independent and multi-disciplinary experts in design and development. A well-rounded assortment of related perspectives is made possible when the review committee includes architects, urban designers, landscape architects, and engineers as well as citizen design advocates.

Most review committees are advisory, providing impartial advice to planning commission, though some have the legal authority to make binding decisions on design matters. Advisory review can be more subjective than binding review, which must follow more precise standards. Planning offices, local universities, and not-for-profit agencies in some communities have set up urban design studios or engaged a staff designer to assist in spatial aspects of design review.

First in schools and then while working in studios, designers become accustomed to the culture of pin-up design review. The review gives the designer an opportunity to appreciate how different people with differing perspectives perceive designs. Constructive comments can add significant value to the education of the student and work of the professional. Design review offers the same advantage in a public setting.

Rural regions and smaller cities that have a limited pool of expertise rely on trained city staff or retain the services of an architect to comment on proposed buildings.

Different strokes

Here are examples of the varying organizational methods of design review that governments use:

• In the mid-Hudson region of New York State, Dutchess County has a development and design coordinator, a trained urban designer who provides advisory site plan design review and planning services upon request to 30 municipalities.

• In older cities with a historic preservation program, the staff person is often the city architect.

• In Flagstaff, Arizona, the city architect also assists the planning staff with design review of development applications.

• Nashville has an in-house design studio with trained staff that assist with design review.

• Seattle employs a trained staff to review smaller projects, and also has several entities that are responsible for design. The Seattle Design Commission reviews design of public projects. Private development projects are reviewed by seven design review boards that cover different geographic districts.

• In Vancouver, British Columbia, a peer review panel provides urban design advice to planning staff. Similarly, in Dallas a peer review panel provides feedback on projects within tax-increment financing districts and designated planning areas. The city manager or a willing applicant can also request design review of a project.

Cities can define the scale and significance of projects that require some form of design review. Design review is conducted on behalf of the public and therefore should welcome public involvement. The formality of the podium-and-dais setting and a public hearing format constrains the creative flow of ideas and dialogue. A charrette pin-up setting or desktop review is more conducive to a productive discussion and exchange of ideas.

Funding

Cities usually charge a fee to recover procedural costs. For review by the town architect, developers can be required to pay the architect’s fee. This fee is a small fraction of the total development budget; developers are usually happy to pay for the expertise that builds on the skills of their design team.

Over all, design review has many advantages, and the concerns can be easily addressed.