Assessing Criticisms Of Form-Based Codes

Originally published in Better! Cities & Towns, April-May 2013.

Market share is a common metric for measuring success of a product. Since their resurrection in Seaside 30 years ago, roughly 300 form-based codes (FBCs) have been adopted. Many of these codes are for small specific areas, not the entire city. Overall, less than 0.2 percent of US cities have adopted FBCs. Why have we not gone to scale with these kinds of codes?

By their very nature FBCs faces many hurdles. Over the last century, we have separated zoning standards from physical planning, leaving out place-making. FBCs are now trying to make up for this all at once. The planner’s concern is we don’t have the capability to do it in-house and the money for consultants has dried up. We have to overcome the legacy of the planning system we have inherited and undergo a generational shift.

Bureaucracy and inertia make it difficult to escape from entrenched old ideas that are hard to change. While Euclidean zoning was born before the depression, it came to age in a rapidly growing post-war economy. FBCs are much more difficult to institute as they seek to replace an existing system in a much slower economy.

Critique of FBCs

One premise is that if people are attacking, you are probably making a difference. Change requires revolution, which tends to be rough and takes time. However, codes inherently are not perfect. The latest FBCs are better than the last one we wrote and we are constantly learning and making adjustments. It is in this spirit that we seek to understand some legitimate complaints against FBCs from the points of view of various stakeholders:

Designer’s perspective: FBCs are ideologically based and overly prescriptive. Some fear that a one-size-fits all, a FBC template may not address community context and character. Even if the community desires it, some codes are overly restrictive, controlling too much — leaving little room for discretion and creativity. Supporters of FBCs should decry such codes — they are just as bad as a loosely written code. Codes should balance predictable results with flexibility and creativity.

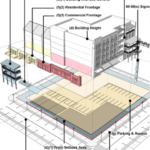

FBCs regulate most of the same elements designers must address under Euclidean codes, but with emphasis on the form of the public realm rather than compliance with abstract numerical ratios. Euclidean zoning offers token participation in the form of a public hearing at the end of the process. In contrast, FBCs are developed under an open participatory process that begins with the meticulous study of the existing physical context and character of a place. The most critical instrument of FBCs is the regulating plan, which unlike the land use zoning map, is based on development intensity and character, on a block-by-block and lot-by-lot basis.

Engineer’s perspective: Like Steve Job’s did at Apple, FBCs put good design before technical constraints thereby challenging the engineers to do their very best and not just rely on pre-ordained liberal safety nets such as the AASHTO Green Book, created by the professional organizations. “Transportation should be a means to an end, not the end in itself,” is a common adage at Nelson\Nygaard Associates, a transportation planning firm. The early and often participation from technical experts during the drafting of a FBC encourages the spirit of working together and breaking down silos.

Property owner’s perspective: Incremental redevelopment, the transition between old and new, can be awkward and painful. Requiring additions to viable uses and structures now deemed non-conforming by the new code to comply with a new system and standards, for example, is always a tough sell politically. Codes must be calibrated to accommodate transitional markets that can over time attract and evolve to the final desired market.

Planner’s perspective: Skepticism about success and training poses an uphill challenge. FBCs are seen as a tool developed by architects for planners — the two groups that were long separated by the universities and their differences reinforced by professional organizations. Further, the tool is perceived as largely consultant-driven, generating higher fees for more complex codes. Municipal planning and engineering staff are trained in Euclidean zoning with its restrictions and check lists. A FBC relies on the implementer being more of a generalist. The generalist has an appreciation for architecture, engineering, urban design, landscape architecture, project programming, and retail and commercial economics. Younger professional staff members are beginning to be exposed to this approach through education, seminars, and conferences and are generally more receptive to FBCs.

Planning educators perspective: Planning schools don’t find it necessary to teach physical planning as a core competency for a professional planner. A few years ago the Planning Accreditation Board debated removing urban design as a core requirement for planners. In cases where planning schools are housed with architectural schools, the architects don’t teach FBCs because it constrains creative process of object buildings.

Professional organizations: Most members within professional organizations use Euclidean zoning so switching to FBC would be going against the norm. However we have tried the Euclidean framework for almost 100 years. It has failed to produce places of lasting value and is not likely to repair and restore the failing commercial corridors, office parks, shopping districts, and subdivisions. Codes are the number one tool for implementation and planners are in charge of the codes. Professional organizations can provide leadership in the field of regulatory reform.

Misconceptions

The failure to understand the purpose and technique of FBCs cause many to stand on the sidelines. Common misunderstandings include:

FBCs are too restrictive

FBCs’ focus on physical vision is perceived to force a narrow range of design options. However, both FBCs and conventional codes establish controls on development. FBCs emphasize standards that shape the collective public realm and offer a great deal of flexibility in the individual private realm. Standards for the public realm are based on community’s vision. Conversely, Euclidean codes control the use of the private realm with vague standards that fail to conceptualize a cohesive public realm. FBCs’ clear and precise standards, streamlined and predictable process, and predictable outcomes have opened development potential within numerous communities.

They ignore market realities

It is a widely known best practice to study the market potential before developing regulations. Market studies are more common with form-based than conventional Euclidean codes. In form-based coding, it is much easier to align the form, uses, building types, and infrastructure with market potential. Why? Because FBCs are an end-to-end integrated product that brings together the various disciplines of planning, design, economic development, engineering, and public safety early on to perform in unison. It becomes possible to analyze the community-supported vision from every point of view, to figure out the cost, and understand how various public and private partners can implement that vision. The results are therefore more predictable. At the same time, a lighter focus on use allows buildings to be nimble to the market.

A one-trick pony

A common misunderstanding is that FBC practitioners use the same playbook with one protocol, method, and template for every situation. Some critics find FBCs appropriate only for greenfield sites, and not appropriate in urban areas.

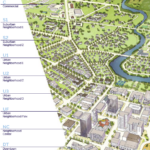

While the language of coding is common, practitioners employ different syntax and dialects. FBCs can be used to protect or transform an area. The applications range from the region to the neighborhood, integrated by a common thread to creating authentic, livable and lasting places.

Conceivably, FBCs could be written to facilitate sprawl. Similarly, the integrated platform of FBCs is better equipped to address the natural environment, affordable housing, and historic preservation. But if for some reason a community decides to not address these issues in their codes, this is not a weakness of the tool, but operator’s error.

Hybrid just sounds better

Hybrid implies the best of both worlds with more flexibility and less controversy. The term “hybrid code” confuses people as it has been used in a couple of ways. The first use of hybrid code is the method in which design guidelines or standards are added to a Euclidean zoning format. Despite the attempt to introduce design, the focus of such codes continues to be on control of density and uses.

This option leaves lots of room for subjective judgment when the codes are applied thereby compromising clarity, and predictable outcomes and processes. Avoiding tough issues for more flexibility fails to produce the results imagined in the vision and disillusions the public to question the efficacy of coding and planning.

In the second preferred option, also referred to as hybrid codes, FBCs are adopted for small areas within a city where walkable urbanism is desired. These FBCs are carefully integrated into the existing citywide Euclidean zoning platform. This option really does offer the best of both worlds.

What can we do to fix it?

We should ensure that the different professional organizations, media, conference organizers, seminar instructors, and the public get the facts correct. People will report what they hear, so it is important they have the correct information and easy access to the experts who understand form-based codes. Plenty of factual information exists and should be channeled to get proper media coverage.

FBC practitioners should refrain from overselling FBCs. It’s only a tool — not a panacea for the absence of good planning. Overselling hurts the product, as focus shifts to what it cannot do versus what it can do. People resist agenda-driven influences, if offered “fixes” they do not want or need. It’s more effective to influence than persuade. Our focus is to inspire lasting buy-in and commitment by painting a picture of a better place. In addition, practitioners must be prepared for lengthy follow-up sessions with implementing staff. This may include training sessions and assistance with project review.

Planners should reclaim their heritage in physical planning and design and lead this effort. Unlike conventional Euclidean codes, FBCs require multidisciplinary skill sets. Overcoming the usual disconnect between planning and design, large cities such as Nashville, Portland, Seattle, Boston, Los Angeles, Chattanooga, Charlotte and many others have urban design studios that are involved in design of spatial elements for short- and long-range planning projects. Smaller cities can bring attention to the design and coding of the public realm by bringing on a staff urban designer, landscape architect, or town architect.

Planning organizations and universities should offer urban design as a core course and the planner’s certification exam should test for competency with physical planning.

Conclusion

Market share is not the only metric for measuring success. Easy to use great products that have the ability to change people’s lives prevail in the long run. In 2010, Apple surpassed Microsoft as the world’s most valuable technology company. It had just 7 percent of the personal computer market but it boasted 35 percent of the operating profits. The market for PCs is shrinking while Macs are growing. As fuel prices soar over the next few decades, municipalities must be prepared to shift to a much more sustainable urban form. This can be accomplished with FBCs.

The good news is that the majority of these codes have been adopted in the past 10 years, so there is momentum. “As the economy recovers and more built results can be seen, this will likely cause an escalation of demand for FBCs,” says Carol Wyant Executive Director of the Form Based Code Institute. In recent years, a number of big cities have either adopted or are developing FBCs — this has raised the FBC profile and is inspiring others to follow suit.