Zoning and Streets: Uniting or Dividing Communities

“Form-based codes aren’t cheap. If we keep the existing zoning map and add some building-form standards, we’d be almost there.”

Some planning directors have had these hopeful thoughts when deciding whether to pursue a form-based code. The question acknowledges the need to make changes to zoning, but naively hopes for simple tweaks. Zoning that effectively shapes and strengthens communities requires more than this. If zoning is to work, it needs to be in the service of making streets work. The proper platting of zones makes it possible to site buildings to shape streets. Many historic zoning ordinances did this, supporting streets as valuable spaces in the life of the community. Zoning in recent decades too often does not.

Streets are the public setting for human commerce—they are where we walk, shop, see our neighbors, and learn a lot about what it means to be human. What happens on private properties—the primary consideration of most zoning ordinances—shouldn’t be treated in isolation from the streets that border them.

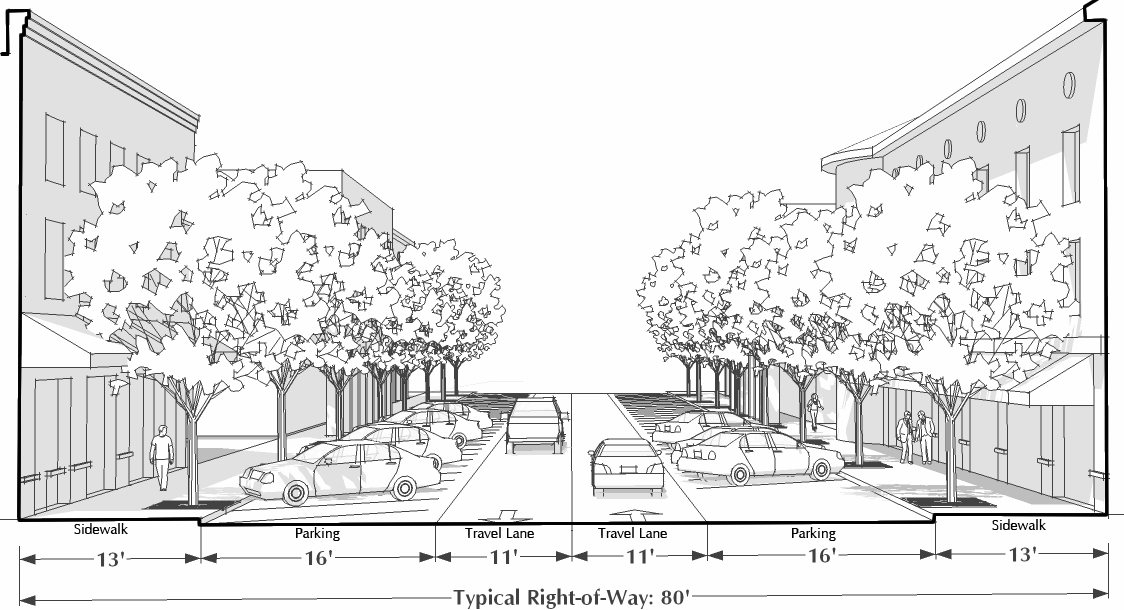

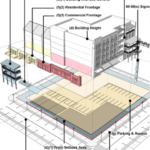

Building-form standards in a form-based code govern physical disposition of buildings in relationship to the streets they face. The functions of streets and buildings need to be coordinated. Adding to zoning ordinances building-form standards that ignore the quality of streets makes little sense. Building-form standards include design standards like building distances from sidewalks, how much buildings fill the frontage of their lots, transparency of the façade, and accessibility of entrances from sidewalks. They can also give identity to streets by regulating how tall building should be in relation to the width of the roadway and assigning particular building types for that street: shop front, row house, live-work, single-family detached, etc. Contemporary zoning’s focus on private property often gives large areas identical regulation without attempting to give place identity to individual streets. The increasing size in recent decades of zones exclusively allowing only single-family detached houses has compounded the problem.

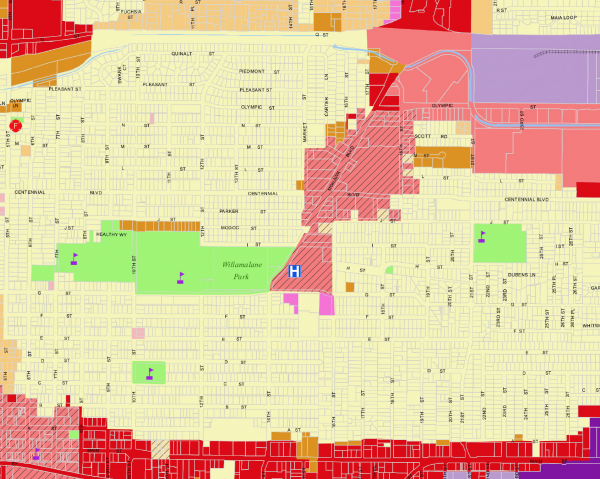

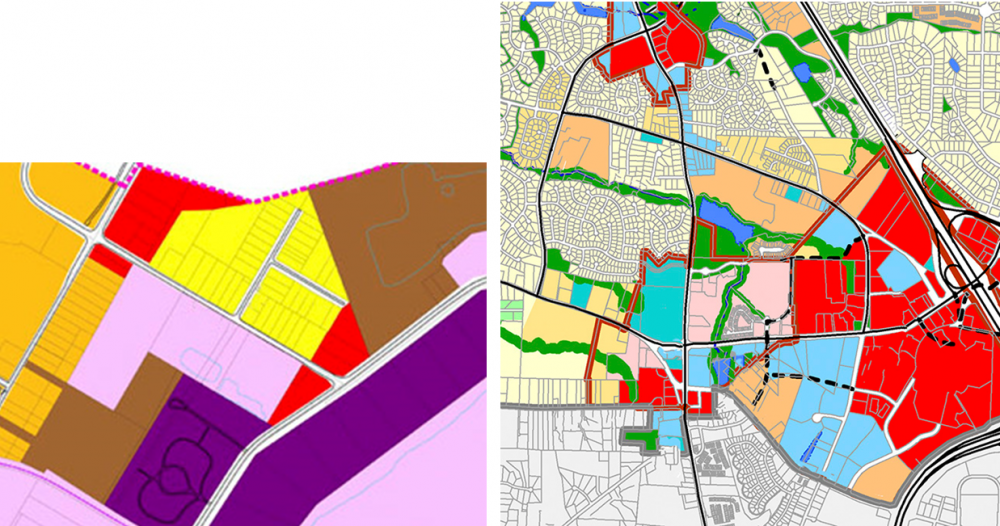

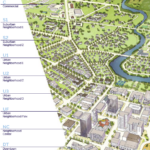

Large zoning districts that lack consideration of individual streets does little for neighborhood identity.

Including mixed-use zones on existing zoning maps usually isn’t the positive improvement people hope for. The Washington Post described my community—El Cerrito, California, north of Berkeley—as one of the most progressive in America. In a progressive spirit decades ago the city added a new zone to its zoning map that planners thought might promote a walkable area near a train station. The mixed-use zone seemed like an easy fix that didn’t question zoning fundamentals. Instead of a zone that allowed only one land use, the thinking was that mixed-use zones would fix single-use zoning by allowing things like main-street-style buildings with shops on the ground floor and residences or offices above. Non-profit public health groups have also advocated for mixed-use zones as a zoning fix that will increase walking. Yet El Cerrito’s mixed-use zone had no requirements for how buildings relate to streets. It couldn’t deliver the walkable streets that people hoped for. What finally got built is a strip shopping center with a big parking lot out front.

Too often with conventional zoning, streets are merely treated as the boundaries of land-use zones. The zone on one side of the street is one land use, and the zone on the other side is another. But people look to streets to be symmetrically shaped on both sides by compatible building forms that face the street. A street should be a connecting spine that knits a neighborhood together, not a dividing line. Too many zoning maps, especially maps from recent decades have chopped up the communities into pieces, adding to the increasing social divisions in our society.

Land-use zoning too often treats streets as land-use boundaries undermining streets’ role as public spaces. Above we see color-coded land-use zones that fail to encompass both sides of streets.

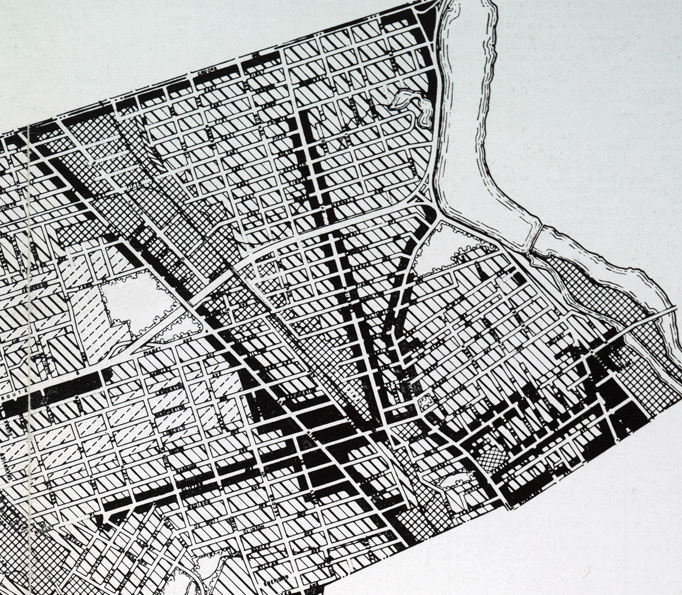

It was not always so. Zoning earlier in the 20th century was used to secure the identity of streets. Residential streets were generally not divided down the middle. And commercial streets were symmetrically zoned for clear identity. In the historic zoning map below, zones were carefully mapped to avoid the bisecting of streets into opposing zones. The commercial streets, marked in black on both sides, especially leap off the page. There is no doubt that the roadway and the properties along it were considered as an inviolable unit.

Historic zoning maps were more supportive of street identities.

Nevertheless, if a zoning map like this survives intact to this day, the quality of streets is still not guaranteed. The development norms that the original mapmakers took for granted have eroded. Nowadays buildings face away from streets, vary greatly in their distances from sidewalks, and are vastly out of scale with adjacent buildings. It’s going to take more than a simple tweak to fix even the historic zoning maps. The community has to do the work of determining the building forms that will restore the unitary character of their streets.

Streets should not be at the edges of our attention. They need to be at the center.

Building-form standards and their assigned zones that tie both sides of the street together, make possible great streets.

(Image courtesy of Spikowski Planning Associates and Dover, Kohl & Partners)

“Form-based codes aren’t cheap.”

Exactly. How convenient that the Form Based Code Institute would recommend this. After all, the FBCI board is made up almost exclusively of consultants that charge municipalities big money to write new codes for them. Of course they’re not going to recommend the smaller tweaks that can often do a lot of positive good and are much more economically, administratively, and politically pragmatic.

I’d much rather have a community with a revised standard zoning ordinance than holding out hope for the political will to do a wholesale zoning rewrite. Half a loaf is far better than none.

This is something important for Jefferson Parish/County, LA to consider right now as they did the same thing an indeterminate time ago (added an MU zone to their otherwise conventional suburban zoning ordinance) and are now moving on to more progressive and ideological goals (bicycle master plan and complete streets) with the assumption, as far as I can tell, that this alone will suffice in making the necessary changes.