Webinar recap: Parking reform for 21st century communities

“Parking reform for 21st century communities: getting more out of public space,” was a joint webinar between the Form-Based Codes Institute and the State Smart Transportation Initiative. Speakers discussed the steps taken to rethink parking policies and prioritize people in public spaces in Hartford, CT and Atlanta, GA. A recording of the webinar is now available. You can also read a recap below.

Many American cities were consumed by expansive surface parking lots and hulking parking structures during the highway building boom of decades past. At the time, city leaders adopted baseless parking requirements that mandated a certain amount of new parking when building housing, restaurants, bowling alleys, supermarkets, and more. It has fueled sprawl to this day and dedicates valuable real estate to the storage of idle vehicles. Now, there’s an estimated two billion public parking spots for about 200 million cars nationwide—an unprecedented waste of public space that contributes to traffic and congestion, dangerous conditions for pedestrians and cyclists, and unsustainable costs for residential and commercial development.

Luckily, a growing number of communities are reversing this trend. And at Smart Growth America, we’ve found that a modern approach to parking policies, especially when integrated with form-based zoning standards, can create more walkable development and cut traffic, improve the public realm and housing affordability, and increase transportation equity.

A discussion recap

Chris McCahill, Deputy Director of Smart Growth America’s State Smart Transportation Initiative (SSTI) kicked off the webinar by outlining the smart growth lens to parking. As the crucial link between transportation and land use, parking policies must respond to community context, address local goals like housing affordability or multi-modal transportation, and be managed accordingly. But the American landscape suggests our attitude toward parking is inherently unsustainable. At best, we’re dedicating one space for every car in places like New York City where most households do not own a car, but nationally there are eight spaces for every car and in some cities it’s much worse—a startling 19 spaces per vehicle in Des Moines, and 27 in Jackson, WY.

Most communities adopted minimum parking requirements in the 1970s on the premise of guaranteeing parking on every lot. Developers are forced to include unnecessary amounts of parking which has spurred serious financial repercussions. When a single parking space costs upwards of $20,000, developers have little choice but to pass those costs on to renters, pushing affordable housing (and small business success) further out of reach. And where there’s structured parking, about $1,700 is folded into apartment costs every year.

Hartford parking inventories: 1960 (left) vs. 2000 (right). Credit: Chris McCahill, SSTI.

The way we manage our parking also determines the way we get around. Much like highway widenings induce more traffic, which is chronicled in a new report by Transportation for America, more parking also leads to more driving. Abundant parking at home and the workspace triggers an automobile default in regional and local commuter behavior, even if the trip is well-served by transit.

“If we aren’t careful about parking policy, we could seriously undermine a lot of other work that’s being done to manage traffic or increase walking, biking, and transit use.” – Chris McCahill

Chris concluded with a promising tool several communities are using to adjust over-parking—a demand-centered approach detailed in SSTI’s Modernizing Mitigation report—where parking minimums are replaced with a points system that rewards developers for building less parking and for taking steps to support walking, biking, and transit.

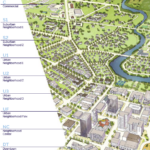

Sara Bronin, University of Connecticut Law Professor and chair of the Hartford Planning and Zoning Commission, focused next on her city’s revolutionary parking reform initiated in 2016—making it the first major city in America to do so. Hartford’s centuries-old development pattern should lend itself to prioritizing people over cars, but considerable amounts of dense mixed-use development have been replaced by surface parking over the past 50 years. Underutilized parking structures and corner lots now disrupt the historic, human-scaled buildings and blocks that characterized the city.

(Image: Sara Bronin)

Luckily, a number of factors helped propel a citywide zoning overhaul in 2016. Residents made it clear they favored walkable mixed-use development over Hartford’s growing auto-dominated landscape, and surveys found a third of households didn’t own a single vehicle. And despite promising gains in transit ridership, Hartford’s transportation insecurity reached 26 percent, which soared above Connecticut’s average. These trends catalyzed four key changes to the zoning code:

- Fewer cars: The city eliminated parking minimum requirements for all types of development citywide except for car sales lots. Parking maximums—which cap the allowable amount of parking—now take precedence and thoughtful design requirements (i.e. buffers and landscaping) enhance the public realm.

- More bikes: Many employers are now required to offer shower and changing facilities, and must satisfy the city’s minimum short- and long-term bike parking requirements.

- Complete Streets: Streetscape requirements that support all modes and abilities are integrated in the zoning code and apply to development across the city. Now, less land is devoted to auto-oriented uses (drive-thrus, car sales, etc.) and more land is zoned for mixed-use.

- Transit-oriented development: Buildings that fall within Hartford’s TOD overlay zone (primarily around CTfastrak stations) must be three to eight stories.

Hartford’s efforts to curb excessive parking isn’t slowing either. Now, the city is determining the best way to encourage property owners to convert surface parking lots into more valuable uses. They are exploring parking lot license fees, land value taxes, and stormwater utilities that charge for impervious surfaces. And finally, the city is interested in doubling down on its bus service.

Eric Kronberg of Kronberg Urbanists + Architects (KUA) then turned the conversation to ongoing efforts to remedy parking in Atlanta. Guided by Atlanta City Design, Eric and his firm led a zoning diagnostic that would help “transform the city into the best possible version of itself” beginning in 2015.

Rather than embarking on a five-to-seven year process for a full zoning rewrite, KUA and the City of Atlanta decided to first address quick-fix problems with the current ordinance. The laundry list of improvements included a missing middle zoning category, neighborhood design standards, and reduced parking/loading requirements. The latter initiated the following:

- Shared parking citywide: Applies inside and outside the Beltway. Shared spaces can be located onsite or offsite from participating properties and managed by time-of-day to smooth out parking demand.

- Parking minimums eliminated within 1/2 mile of transit: Applies to all uses, rail and bus transit.

- On-street parking counts toward off-street parking requirements.

- Parking minimums eliminated for buildings built before 1965.

- Parking minimums eliminated for projects that meet inclusionary zoning requirements.

Advocacy and work on parking reform must be calculated. Adjustments to current policies need to reflect the local context—and they rarely succeed without smaller, incremental steps. Eric shared several examples his firm has identified to show how different communities are tackling the problem across the country.

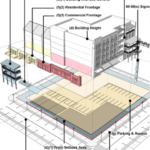

Credit: Kronberg Urbanists + Architects

Credit: Kronberg Urbanists + Architects

Questions?

We had so many great questions during the Q&A section of the webinar that we couldn’t get to all of them. Here’s what our speakers had to say about the ones we missed.

What’s the best way to balance the parking needs of state employees that live some distance from Hartford with the needs of Hartford residents who have less need for such large parking installations?

Chris: As an outside observer, Hartford’s approach has not been to make parking harder for suburban commuters. Instead, they’re mainly interested in making development easier (including more downtown housing options), partly by eliminating tough parking requirements, while improving local transportation options. The State’s recent commitment to regional transit—a BRT line and new commuter rail service—has also helped. The policy changes happened fast but the outcomes will take time.

[/collapse]

[collapse title= “In Atlanta, can on-street parking spaces be allocated to multiple users?”]

Eric: On-street parking can only count towards the property directly adjacent to the parking on that side of the street. However, we do have shared parking provisions now that can allow uses/lots to share parking with other lots within a set distance, so there are roundabout ways to share this parking.

How many people come into Atlanta for work from surrounding municipalities? In Toronto, there are multiple municipalities with a very large number of people who commute in by car and would not like parking restrictions.

Eric: A large, large percentage of folks commute in, and commute out of the city for employment. Ultimately, charging a fair price for parking is critical from a transportation management standpoint. The City of Atlanta is getting better at charging for on-street parking, and the expectation that people will need to pay for parking in multiple districts is increasing daily. People always prefer something for free instead of paying for it, so upset commuters is a logical outcome of places growing and working to become more walkable.

With the reduction of parking lots (or total number of spaces), has either city experienced any increase in congestion (or other impact) downtown resulting from drivers searching for parking (some studies cite up to 30 precent of traffic)?

Eric: I haven’t seen studies on this, but we are doing a better job charging for on street spaces across the city, helping to ensure parking spaces are available and minimizing congestion circling.

Chris: The 30 percent statistics should be taken with a grain of salt. A recent study led by Adam Millard-Ball at UC Santa Cruz points to the fact that cruising in San Francisco and Ann Arbor is as low as 5 percent. The study explains that as parking gets scarce, people are more willing to take the first available spot and walk longer distances, so cruising potentially goes down.

My city is considering developing a city owned surface level parking lot with housing and replacing most of the parking. What tools can the city use to support people that rely on the parking during construction?

Eric: Look to leverage on-street parking as much as possible. Streets are often wide enough to support this parking, but it is not explicitly clear to drivers that parking is an option.

Can any of these strategies be scaled down for more rural cities with less new development and limited tax base?

Eric: Same answer as above. On-street parking is some of the most cost-effective use of asphalt for vehicle storage out there.

Chris: Consider starting with parking meters and commit the revenues to local improvements through a parking benefit district. That can also be a catalyst for discussing other policy changes.

What was the response from the local Chamber of Commerce groups? They often believe the parking is required for economic growth

Eric: Our Regional Commission and Chamber of Commercial generally realize that Atlanta won’t make it with automobiles as our primary mode of transportation. We also have had a massive shift of major corporations wanting to be located next to transit stations. So the chamber of commerce (and state level recruiters) understand that walkable amenity next to our MARTA is the best way to attract major corporations. Putting all that next to a major research institution like Georgia Tech is why Midtown Atlanta is on fire from a development standpoint.

Have any of your solutions discussed a parking buyout incentive to mode shift employees?

Chris: At eight firms in California, Donald Shoup found parking “cash out” encourages about 13 of every 100 employees to change how they get to work. During the Webinar, I also mentioned Travelers Insurance in Hartford, which started charging employees for parking and saw a similar shift.

Cleveland has a local lending and real estate community that is very hesitant to offer capital for projects that have little to no parking, even in areas with rich transit amenities and density. What tools were deployed for getting around that lending obstacle in your cities?

Chris: Local regulations such as reduced parking minimums or even parking maximums can help level the playing field so lenders and developers are less concerned about competing in the market. Without minimum requirements, developers also get creative about meeting parking needs, such as relying more on nearby, off-site parking.

Reducing off-street parking is great, but incentivizing on-street parking reduces street area available for bike/ped/bus infrastructure. So does switching the parking burden onto the street really help promote mode shift?

Eric: This should be tackled from a network standpoint. Prioritize your bike infrastructure pathways, and let those streets have a priority for bike lanes. Streets not on that priority network can prioritize on street parking.

Chris: On- and off-street parking should be thought of as part of the same system. A key difference is that on-street parking takes up far less space and it can be more easily shared among different uses at different times of day. That said, it usually needs to be managed appropriately through pricing or permitting. And there are still plenty of instances where sidewalks, bike lanes and bus stops take higher priority. There’s no hard rule about what’s best in any given scenario.

Has there been an increase in the amount of variances, waivers, etc. from developers wanting to exceed parking maximums?

Eric: Not much in Atlanta, but our maximums are pretty generous.

Chris: The most pressure might be for new office buildings, which are being used more efficiently to fit more employees per square foot. On top of that, many developers still see employee parking as a critical amenity, even in many downtown locations where that might not be the case.

My very small, very isolated tourist city (Moab, UT: 5,000 permanent residents, 20,000 visitors per night) has received a full grant from Utah DOT for a parking garage, to be located on an existing lot which is deed restricted to use as parking. As our first garage, there’s significant pushback to the idea. It seems like, given the circumstances, it will give us some additional parking capacity and breathing room to implement more progressive parking policies. Can you opine on the role of garages for cities desiring to move towards more people oriented urban planning?

Eric: What could you do with those funds instead? How much streetscape improvement could be addressed in conjunction with a plan to expand on street parking, pricing, and wayfinding?

Chris: A key opportunity with building a new garage is that local governments can let nearby developers lease existing spaces rather than building new capacity on their own. Lowell, Mass. is a good example.

Are developers who choose to minimize parking asked to promote or financially support public transportation as part of their development projects?

Eric: Not directly in Atlanta, but low parked projects near transit should naturally make using transit by riders more attractive, thereby adding benefit and support to the transit system.

Chris: Developers can sometimes pay a fee in lieu of parking, which the local government can use to support transit, biking, and walking. In Sacramento, developers can provide less parking when they implement a transportation management plan, which can include transit subsidies. SSTI outlines similar programs in its report, Modernizing Mitigation.

We have found that even with data showing overparking and issues associated with parking provision, public and decision-makers still resist reforming parking policies. What do you do if they are even denying what the data shows?

Eric: Narratives sell, data much less so. You need compelling stories to show how your city could be a better, more inclusive place through better policy. It seems like Hartford did a good job blending stories and data to build a strong coalition.

Chris: Focus on the benefits, often by pointing to successful historical areas or central business districts. Development costs and other barriers to development are much lower; the walking environment is more pleasant; and parking can actually be easier and more reliable due to pricing or on-street regulations.

Allowing on-street parking to count toward minimum off-street spaces seems to invite double-counting. How can this be avoided?

Eric: On-street spaces tend to turn over 3-5 times as much as a private, off-street space, offering much more utility in a lot less asphalt. I’d recommend not worrying about possible double counting. It’s a feature, not a bug.

Chris: There are useful examples of how to share parking among uses at different times of day. See “Shared Parking” by ULI or the zoning codes in Lowell, Mass. and Hartford, Conn.

Shopping center parking lots, sparsely used 11 months a year are overflowing in December; How can this surge be handled?

Eric: Redevelop them with mixed-use approaches that can utilize the parking much more fullying. And I’d challenge the statement that those lots are actively full for an entire month. I tend to see the rush to the mall happen on December 20-24, when folks realize Amazon can’t ship their presents in time (and even then there is often parking available, it’s just not right next to the door)

Chris: Consider pervious areas or nearby lots that can serve as overflow parking, temporary shuttle services, extended hours to spread out the demand, and providing information and incentives for alternative travel options.

How does the reduction of parking spaces impact underserved low-income commercial & business districts?

Eric: Requiring parking spaces is one of the greatest burdens on these commercial areas, greatly handicapping the ability for businesses to grow, change, and thrive.

Chris: Folks in low-income neighborhoods typically drive and own cars at lower rates, so they might benefit more from safer walking conditions and better transit service than from parking. They also end up paying the hidden costs of “free” parking everywhere they go. A recent study from UCLA found that parking garages add $1,700 per year to apartment rents and cost the average carless renter more than $600. When parking gets scarce, the revenues from parking meters and permits can be used to offset the cost burdens for low-income households and make transportation investments that serve them well.