FBCI Holds Symposium to Explore “Urban Form as a Framework for Healthy Communities ”

“I have two doctors: my left foot and my right foot.” — G. M. Trevelyan

Medical breakthroughs such as new vaccines, therapeutic drugs, surgical procedures and early detection screenings have improved treatment of many illness and injuries. But less attention has been paid to finding ways to prevent the development of avoidable health problems and risks such as diabetes, heart disease, asthma and trauma caused by traffic accidents. There has been some improvement over the past several decades, most notably a nationwide reduction in smoking rates and improved nutrition. However, a major contributor to unhealthy and even dangerous lifestyles often is overlooked: the built environment.

This message was driven home by a diverse group of experts during an educational symposium the Form-Based Code Institute (FBCI) held in San Francisco on Feb 16, to discuss how to create built environments that support and improve public health.

For example, because of most people’s relatively sedentary lifestyles, more than 36 percent of U.S. adults are obese, double the rate recorded in 1980, and the rate of childhood obesity has more than tripled, reaching 17 percent, the according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Those affected are at a much higher risk than the rest of the population of developing Type 2 diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, pointed out Richard Jackson, M.D., a pediatrician, professor and former chair of Environmental Health Sciences at the Fielding School of Public Health at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1985, 2.6 percent of the general population — 6.13 million — were diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. By 2014, the percentage had risen to 7 percent, putting almost 22 million people at increased risk for myriad complications, including heart and blood vessel disease; nerve, kidney and eye damage; to gangrene, which can lead to amputation; and Alzheimer’s disease.

Although drugs can help control Type 2 diabetes, simple exercise, such as walking, was found to be twice as effective in controlling the disease and can prevent its onset, said Jackson who once served as California’s state health officer and director of the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health. He cited a study of 3,234 people with pre-diabetes who exercised, including walking, for 30 minutes a day, five times a week over six months. They lost 7 percent of their body weight and reduced their risk of developing diabetes by 58 percent.

Although he has long encouraged his patients to exercise to improve their health, Jackson noted that the car-centric nature of many communities discourage people from walking and may even make it dangerous to do so.

“In many areas, we’ve made homeowners responsible for maintaining sidewalks, with mixed results. That sends the message that the one-third of our population that doesn’t drive doesn’t merit civic support or the expenditure of tax dollars,” he explained.

But it is not enough to make it easy for people to adopt this form of exercise to the extent that it becomes therapeutic, he added.

“We won’t get people to walk until we make the impulse to do so irresistible, by providing inviting vistas, plenty of shade and compelling pedestrian destinations.”

In addition to writing two books on the unhealthy effects of urban sprawl, Jackson hosted a public television series in 2012 that highlighted cities, such as Boulder, Colo., possibly the healthiest city in the nation, which promotes cycling, walking and other athletic activities, and Elgin, Ill., which revitalized its downtown to discourage residents from driving long distances to schools, stores and restaurants.

Long daily commutes and the isolation of suburban living limit opportunities to exercise, socialize spontaneously or engage in casual interaction often triggering depression, which is the second most prevalent disorder in America, Jackson said. The CDC reported in 2011 that antidepressant use had soared by 400 percent since 1991. He praised the inviting architecture and open, sunny, green-space-filled areas around many buildings at the University of California, Berkeley as examples of how physical space can foster good mental health.

“Walking around here makes me happy. Just getting out in the fresh air among surroundings like these is a cure for depression,” he added.

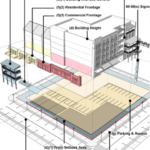

In his presentation on form-based codes (FBC), Dan Parolek, co-principal of Opticos Design, an architect and urban planning firm in Berkeley, Calif., pointed out that these codes are intended to ensure the development of an “urban walking environment that ties back to public health.”

He referred to Euclidean or use-based zoning, which has been widely adhered to for 100 years, as an “outdated operating system,” that no longer reflects or provides the types of communities in which many people want to live, work and socialize. He likened this type of zoning, which still guides most community planning, to “trying to use a Polaroid camera to tweet or text your friends a photo.”

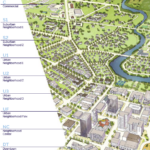

Parolek also noted that over the past 10 years Opticos Design has moved on from writing FBCs for individual neighborhoods and transit corridors to implementing FBC-based strategies on city and county-wide scales. He cited Cleveland as an example, noting that 42 high-priority walkable neighborhoods were defined in the city’s comprehensive plan.

But it is equally important to focus on creating landscapes that ensure pedestrian safety and on how buildings interact with the streets along which they are built, he stressed. In Livermore, Calif., the city manager allowed the firm to incorporate thoroughfare standards into the land development code, “which drove the engineers crazy but it made them talk to the city planners before they changed those standards,” Parolek recalled.

He explained that creating a vibrant urban neighborhood involves more than focusing on walkability or developing mixed-use buildings; planning should be based on a vision of the type of community that will be created and how it will evolve over time.

He decried the “dramatic state of disinvestment in neighborhoods,” that can lead to unhealthy development, such as the establishment of a corner store that might sell liquor but no healthy food. Parolek also stressed that neighborhood revitalization efforts should not lead to the type of displacement that gentrification can trigger but should provide the opportunity for economically and socially diverse neighborhoods.

“High-performance communities are not all about creating a bustling downtown; development can be small-scale, allowing for the construction of a mix of small, medium and large homes, ranging from single-family bungalows to missing middle, cottage core, duplexes and fourplexes.”

After the presentations, Jackson and Parolek joined a panel of health care policy and community development experts who fielded questions from the audience.

One questioner pointed out that the speakers had mentioned several city-driven development projects and asked what role states or the federal government could play to encourage the adoption of FBCs. FBCI Chairwoman Lisa Wise explained that while it is up to local governments to adopt city ordinance’s like FBCs, states can play a role as well. Michigan, for example, is providing training to convey FBC development concepts to people across the state to encourage broad adoption, she noted.

A community can make a strong case for state or federal funding for projects if they can show that the project will contribute in multiple ways to making a community healthier. One example is aligning community planning with efforts to establish or improve a neighborhood’s access to public transit, explained Eric Calloway, senior planner at ChangeLab Solutions, where he develops strategies and tools to help communities support healthy living and sustainability.

Mental health is an important component of overall health. The health care system has not addressed this effectively but is gearing up to do so, said Kathryn Boyle, a project manager for Kaiser Permanente’s Community Health Benefits Program.

“The built environment can and should contribute to that,” she said and stressed the importance of incorporating parks into communities, to spur residents to enjoy the outdoors and socialize.

Although a lot of information has been published on the positive health effects of parks and the presence of tree canopies, more research needs to be conducted on how the built environment affects public health, said Elizabeth Baca, senior health advisor in the California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research.

She noted that that it is easy to measure a community’s impacts on the physical environment by studying water and energy use, air quality and waste production but the benefits or risks posed to overall health can be difficult to analyze.

Jackson pointed out that it is not enough to promote the benefits of developing healthy cities; proponents must also be able to effectively counter the arguments against them. These fears range from gentrification to the development of unsightly skyscrapers to concerns over the availability of parking. He stressed the importance of focusing on both environmental impacts and how building healthy cities will change human behavior.

“It’s important to conduct environmental impact studies on the effects of changing zoning strategies and analyses of how much increasing housing near transit centers can reduce car travel,” he said.