At the Congress for the New Urbanism’s (CNU) Charter Awards Ceremony in Seattle on May 5, the Form-Based Codes Institute (FBCI) announced that Palm Desert, Calif., and Nashville, Tenn., had received the 2017 Driehaus Form-Based Codes Award for their implementation of innovative and effective codes. The Driehaus Form-Based Codes Award is sponsored by FBCI with the generous support of the Richard H. Driehaus Charitable Lead Trust. Nominated codes were critiqued by a four-member jury of peers.

Mention Palm Desert and many attractive features come to mind: mid-century modern architecture, luxury retail businesses, resort living and world-class golf, to name just a few. Walkable neighborhoods, an interconnected network of multi-modal streets and mixed-housing neighborhoods centers are not commonly associated with this widely known desert city, yet those are just what Palm Desert’s new general plan and University Neighborhood Specific Plan call for. The city’s leaders, with the support of the community, have decided that such places are the next missing pieces to add to its attractive repertoire, to diversify its lifestyle offerings as it matures in the 21st century.

Palm Desert was founded in 1945 in Riverside County as a 1,600-acre resort destination for celebrities and politicians on “the Grapefruit Highway” (Highway 111), connecting Los Angeles to Tucson and other destinations east. Its first neighborhood was marketed as a close-knit model of desert living where residents could walk or bike to local shops. Over the next 60 years, the city grew to cover more than 27 square miles based on the prevailing suburban development models of that time, introducing a grid of high-volume, high-speed six-lane arterial streets connecting – and separating – inward oriented housing tracts, and strip shopping centers. The majority of those housing developments were focused on retirement living, featuring golf courses and one-story houses, and big yards for enjoying outdoor desert living.

Looking to the future, city leaders initiated a strategic planning process in 2012, engaging the National Civic League to structure a community-based discussion of the city’s future. The process included a number of community surveys, dozens of community meetings, and a year and a half of work by a number of resident-led committees. The result was the “Envision Palm Desert” report, which identified top community priorities: attracting and retaining younger residents, balancing housing with new local jobs, and supporting higher education. Topping the list of strategies for achieving these goals was developing a “real city center” for Palm Desert and developing new walkable, bikeable, mixed-use and mixed-income neighborhoods both as part of the city center, and in a new university district anchored by a new California State University branch campus in North Palm Desert.

To put the strategic plan into action, the city retained a consultant team led by Raimi + Associates to update its general plan, including a plan to transform the old Highway 111 strip in the center of town to “Boulevard” 111. One block south of 111 is El Paseo, Palm Desert’s very walkable high-end shopping, arts and entertainment street, which was developed, ironically, in the 1970s at a time when so many other cities were letting their main streets decline and moving retail activity to suburban shopping malls. Through a series of workshops and design studies, a new vision for Boulevard 111 was agreed upon, transforming 111 from a “rip” – a physical barrier separating El Paseo from the neighborhoods and the civic center to the north – to a “zipper” that connects them. The team prepared the city center plan as a chapter of the new general plan, and new form-based zoning and public realm standards to implement it.

Based on the success of the city center work, Palm Desert retained the same consultant team – led this time by Sargent Town Planning (STP) – to prepare specific plan and form-based code for a 168-acre city-owned property near the new university campus. In the early work on the plan, the team noted that 200 acres of adjacent, previously planned and entitled – but currently unbuilt – conventional suburban housing tracts separated the city’s land from the campus, limiting connections to trails along arterial streets and overall circulation opportunities. Those previously approved tract maps were on the verge of expiring, and the property owners agreed to be part of the new plan in return for new entitlements permitting additional housing units on the condition that those units be delivered in a form consistent with the vision of the University Neighborhood Specific Plan.

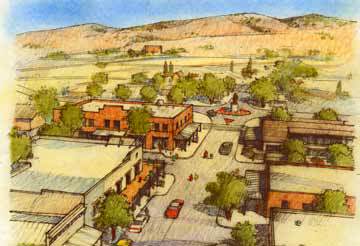

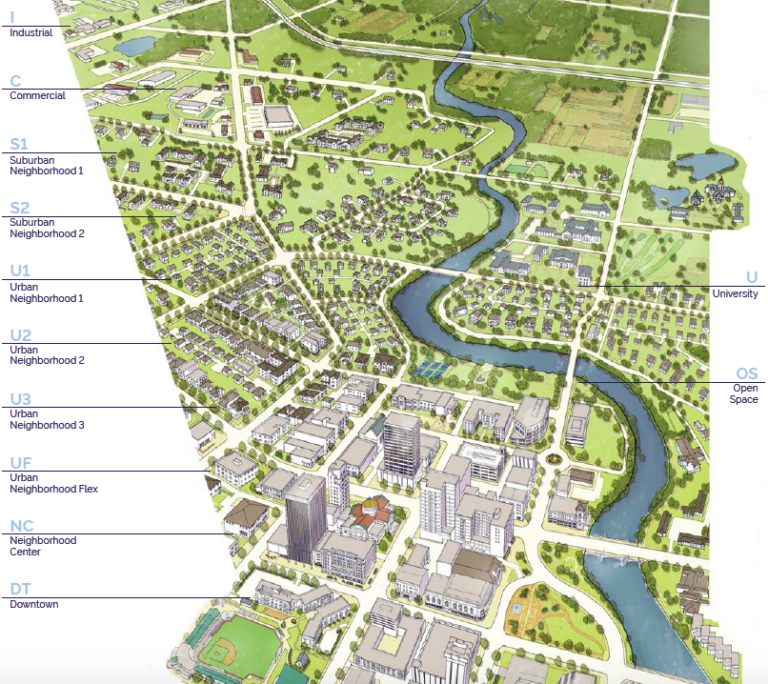

University malls, promenades and other public spaces will contribute to the UNSP’s integrated community character.

The university neighborhoods, along with the planned campus expansion to the east and other adjacent development, comprise a university district of almost 1,000 acres at the north gateway to Palm Desert. Separating the neighborhood from the campus is Cook Street, a major north-south arterial corridor connecting from Interstate 10 to the city center several miles to the south. An important element of the plan is the transformation of Cook Street, which entailed converting the outer travel lanes to on-street parking and bike lanes, thereby calming the traffic and enabling new development to front Cook directly rather than huddling behind walls and parking lots. The result is a walkable mixed-use corridor that reconnects campus to the new university neighborhoods. The STP team engaged the university’s campus planning team and obtained the university’s enthusiastic support for this change. Additionally, a future Cook Street shuttle or bus rapid transit is planned to connect the university district to the city center to the south, along with a potential future passenger rail station.

To structure this new neighborhood, the STP team prepared a conceptual neighborhood plan organized by an interconnected network of complete streets throughout the plan area and connecting to the campus to the east. The focus of the plan is a new, mixed-use neighborhood center around a town green with local retail, restaurants, boutique office space, live-work opportunities, and a range of multi-family and attached single-family housing types. The neighborhoods are planned for a flexible mix of housing types – primarily single family attached and detached – organized around a network of small neighborhood parks and greens, connected by pedestrian-scaled neighborhood streets.

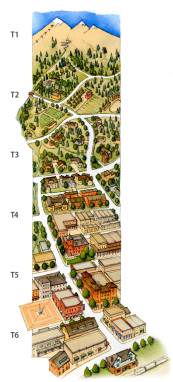

The code’s regulating plan applies three form-based zones to the university neighborhood planning area. The Neighborhood Low zone is intended to create a quiet neighborhood environment with single-family detached housing types on a range of lot sizes, and may include some single-family-attached and small multi-family “house-form” types that are compatible with houses in scale and character. The Neighborhood Medium zone includes those house-form types as well as courtyard housing and multi-family apartment buildings up to three stories in height, with building-scale standards. The Neighborhood Center zone is mixed in use, including ground floor retail, office and housing, allowing bot rental and ownership options. Finally, an Open Space zone reserves key locations for neighborhood and community-serving open spaces, such as the central town green, neighborhood parks of various shapes and sizes, and a large linear natural green space that fronts major arterials along the south and west borders of the planning area.

“In writing an FBC for a large area, which will take many years to complete, a core goal is creating long –term value that will accrue both to the community and to the master developer,” said John Baucke, president and CEO of New Urban Realty Advisors, Inc., who served as theSTP team’s development advisor, contributing a developer’s perspective to the project.

Because the district will be developed in phases over time by multiple builders and probably more than one master developer, and under changing market conditions – the code starts by defining “framework streets” that provide primary internal and external access and connectivity for the plan area, and organizes the planning area into a series of sub-areas. The exact alignment and design of the framework streets is somewhat flexible, as are the final sizes and configurations of blocks and lots, but the basic connectivity and design character are fixed by the plan.

The code starts with a section called “Subdivision Standards,” which walks the user through the process of finalizing the alignment and design of the framework streets, and organizing each sub-area into a walkable neighborhood area. Prior to any development within a sub-area, the code requires that the developer prepare a precise neighborhood plan for that area, defining with precision the layout of streets and blocks, which streets will be connected to adjoining sub-areas, which specific building types are intended, and the design and landscaping of all streets, parks, greens and alleys. Block sizes and shapes are flexible within parameters, with lot sizes and alleys, or no alleys, defined by intended building types and connectivity requirements.

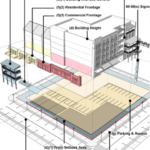

The code provides a system of street typologies, to be assigned based on the intended function and environment of that street (e.g., an active mixed-use center, a neighborhood edge, a neighborhood connector, or a quiet neighborhood street). To further customize each street to its buildings, the code provides a range of public frontage types that describe the design configuration and character of the streetscape elements between the vehicular travel lanes and the buildings. These are calibrated to the intended ground floor use/activity of the adjacent private development, configuring on-street parking, street trees and landscape, street lighting and furnishings, and in some cases bike lanes. The result is intended to be an interconnected, safe, comfortable and attractive, multi-modal network of public spaces that provide unique, high-value addresses for buildings that front them.

A variety of public open spaces including edge greens, attached and detached neighborhood greens, pocket parks, paseos and rosewalks (pedestrian “streets” defined by building frontages), and alleys complete the public realm network. Alleys are required for narrow-lot, single-family and multi-family housing types, and at transitions from residential to commercial ground-floor use.

The code employs simple form-based development standard techniques for all buildings, focused on their size, placement and frontage. Frontages modulate the degree of privacy for ground floor spaces, ranging from low front-yard fences and climate-calibrated landscape, dooryards, terraces, porches stoops and commercial shopfronts and arcades. The code also includes standards for building scale and massing, regulating the expression of horizontal increments to ensure that the apparent scale of buildings within each zone and within each block fall within a harmonious range. Unlike many of the earlier codes by the firm and other West Coast practitioners, the standards do not explicitly include “building types”; rather, they are provided as part of an extensive design guidelines appendix, bound in a separate volume. The guidelines cover a wide range of topics including basic material and technique guidelines, landscape guidelines, and style-specific guidelines for a number of regionally significant architectural styles including Spanish colonial revival, mid-century modern and others.

The code requires that that the Precise Neighborhood Plan assign these elements street by street and block by block, for city review and approval as a unified package.

In preparing the development standards and design guidelines, a universal consideration was the nature of outdoor spaces at all scales. The integration of interior and exterior spaces has always been a defining characteristic of the “desert lifestyle,” including expansive views of neighborhood landscapes through the heat of the day, and the occupation of those spaces on winter days and long, warm evenings. Recent trends in market-based development types in Palm Desert were shifting directly from the very large lot, sprawling one-story homes to very small lot two-story homes with virtually no yard space. The University Neighborhood Plan proposed and intermediate possibility: relatively compact forms of two- and three- story housing that defines comfortable, pleasant, shady, wind-protected yard spaces well-connected to interior living spaces.

The code’s building siting and massing standards – and the building-types in the design guidelines, define such spaces that range from small side-yard patios to modest rear yards to semi-public dooryards, to courts, gardens and rosewalks shared by households in single family and multi-family compounds and buildings. And in the neighborhood center, siting and massing standards are provided to organize buildings around shared plazas, squares, and greens.

Although Palm Desert’s city council was wholeheartedly in favor of the STP’s focus on turning the university district into a connected, walkable community, the development team faced some significant challenges to some of its proposals at first. One such example was the re-imagining of Cook Street.

“Our goal was to transform Cook Street from just another aesthetically unremarkable highway taking drivers through town as quickly as possible, into an attractive, vibrant, business corridor,” David Sargent, president of Sargent Town Planning explained. “Finding ways to slow traffic down was essential to achieving this goal but it triggered push-back from some residents and officials, as you might expect. We were able to calm those objections by including some strategic triggers in the general plan. For example, the lane reductions wouldn’t be implemented until after the student population reached a certain level and a planned interchange has been built a half mile west of Cook Street to siphon off some of the traffic.”

As expected, finding developers willing to buy in to a community of this type requires patience, and it has. While the University Neighborhood Plan was in administrative draft form, a large, well-financed master developer expressed interest in buying and developing the northerly half of the planning area, hiring a land planner to lay out the neighborhoods. That initial concept plan was prepared without regard to the code, minimizing the public realm and connectivity and relegating “pedestrian connectivity” to a trail system running behind lots. The city indicated its support for the model proposed by the plan and code, and authorized the Sargent team to prepare a plan variation that met many of the developers housing type objectives in forms consistent with the plan, which generally was well-received.

“The developer hasn’t lost interest in building on the property and has taken what we did back to the drawing board. In fact, they’re talking about acquiring and developing the other 170-acre parcel, too,” said Ryan Stendell, the city’s community development director. He praised the team’s development advisor John Baucke and economist David Bergman, for helping the team to anticipate the developer’s concerns. “The master developer is moving forward because, looking at the property and the city’s plans for it from a market and financial perspective, it offers a strong potential to generate both short-term and long-term value,” said Baucke.

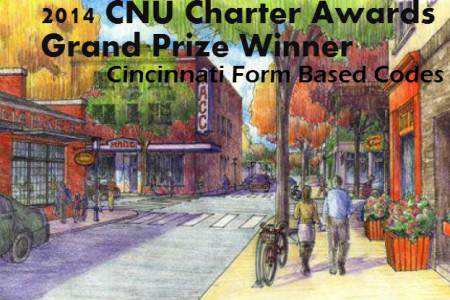

The jury that awarded Driehaus Form-Based Code Awards to Palm Desert, called it “an excellent example for regulating large-scale infill development to produce a walkable place,” and for providing “’a kit of parts’ for creating the fundamental urban form — addressing both the public realm and private development and achieving the ideal balance between predictability and flexibility. It creates a regulatory framework and process within which future detailed planning and development can take place. This code is elegantly designed, with clear and attractive images throughout and an appendix of beautifully illustrated design guidelines,” the jury declared.

Read More →

Wednesday, November 20 at 1 p.m. ET | Register >>

Wednesday, November 20 at 1 p.m. ET | Register >>