Misconceptions About Form-Based Codes

Originally published in Better! Cities and Towns, September-October 2014

Since 1981, approximately 400 form-based codes (FBCs) have been prepared for communities across the US, and as of 2012, 252 of them have been adopted. Eighty-two percent of the adoptions have taken place in the past 10 years. But as exciting as that may be, what’s more exciting is that these numbers are miniscule when you think about how many communities exist in the U.S. If this reform of conventional zoning is increasingly gaining acceptance and being applied to larger areas, why are there still so many misconceptions?

Despite a wide variety of improvements in how formbased codes are strategized, prepared, and used, many of the planners, planning commissioners, elected officials, members of the public, and code practitioners I meet continue to harbor misconceptions or misunderstandings about these codes. Here are the ones I encounter most:

FBC dictates architecture. Some of these codes do prescribe details about architecture, but most do not. Perhaps because many of the early codes were for greenfield projects where strong architectural direction was needed or desired, the perception is that a FBC always regulates architecture. Yet the majority of codes I’ve prepared and reviewed (30 authored or co-authored, 10 peer-reviewed, 9 U.S. states, 2 foreign countries) do not regulate architecture. I’ve prepared codes where regulation of architecture (style) was important for a historic area, but those requirements did not apply anywhere else. The “form” in form-based codes may mean architecture, but not necessarily. Form can refer to physical character at many different scales—the scale of a region, community, neighborhood, corridor, block, or building.

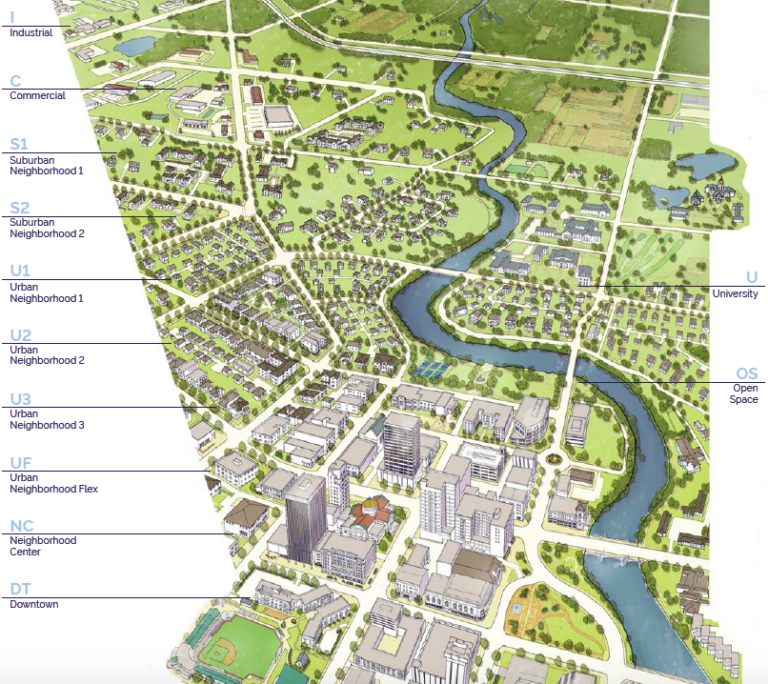

FBC must be applied citywide. To my knowledge, Miami, and Denver are the only US cities that have applied form-based coding to all parcels within their boundaries. In general, FBCs are applied in two ways: to a site to implement a development project or to several areas as part of a zoning code amendment or update. This second category sometimes involves reconfiguration of the zoning code to retain a set of conventional zones for “automobile-oriented suburban”patterns while adding form-based zones for “walkable-ur-ban” patterns. This is called a hybrid code because it merges the conventional zoning and form-based zoning provisions under one cover, in one set of procedures.

FBC is a template that you have to make your community conform to. Untrue. Conventional zoning, with its focus on separation of uses and its prohibition of ostensibly undesirable activities, often conflicted with the very places it was intended to protect. Perhaps what some refer to negatively as a form-based code’s “template” is the kit of parts that repeats from one community to another—the streets, civic spaces, buildings, frontages, signage, and so forth. But a form-based code is guided by how each of those components looks and feels in a particular community. The FBC responds to your community’s character.

FBC is too expensive. FBCs require more effort than conventional zoning—but then, conventional zoning doesn’t ask as many questions. FBCs reveal and thoroughly address topics that conventional zoning doesn’t even attempt. Some communities augment conventional zoning with design guidelines; those guidelines aren’t always included in the cost comparison, and in my experience they don’t fully resolve the issues. A FBC has the virtue of ensuring that your policy work will directly inform the zoning standards. Further, the the upfront cost of properly writing a FBC pales in comparison to the cumulative cost of policy plans that don’t really say anything, zoning changes that require the applicant to point out reality, hearings, and litigation over projects.

FBC is only for historic districts. FBCs can be applied to all kinds of places. Granted, they are uniquely capable of fully addressing the needs of a historic district because of their ability to “see and calibrate” all of the components. Such a FBC works with not instead of local historic procedures and state requirements. This is in contrast to conventional zoning’s focus on process and lack of correspondence with the physical environment it is regulating. While a FBC can be precise enough to regulate a very detailed and complex historic context, that same system can be fitted with fewer dials for other areas.

FBC isn’t zoning and doesn’t address land use. If your FBC doesn’t directly address allowed land uses or clearly rely on other land use regulations, it is an incomplete FBC. Some early FBCs were prepared as CC&Rs (covenants, conditions, and restrictions) because of particular development objectives, and some well-intended early FBCs oversimplified use restrictions. Since then, FBCs have augmented or fully replaced existing zoning, including land use requirements.

FBC results in “by-right” approval and eliminates “helpful thinking by staff.” With so much emphasis on how FBCs simplify the process, it’s understandable that this perception has caused concern. Throughout the FBC process, focus is placed on delegating the various approvals to the approval authority at the lowest level practical. I’ve seen few codes that make everything “by right” over the counter. The choice of how much process each permit requires is up to each community. Through a careful FBC process, staff knowledge and experience does go into the code content through shaping or informing actual standards and procedures.

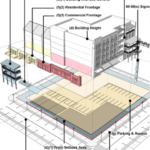

FBC results in “high-density residential.” FBC does not mandate high-density residential.” Instead, it identifies housing of all types—from single-family houses to quadplexes, courtyards, rowhouses, and lofts over retail—and explains their performance characteristics. Density is one of many such characteristics. Through the FBC process, communities receive more information and decide which kinds of buildings they want and where. FBCs enable higher density housing—where it is desired by the community—to fit into the larger context of the community’s vision.

FBC requires mixed-use in every building regardless of context or viability. Conventional zoning has applied mile upon redundant mile of commercial zoning, resulting in an oversupply of such land and many marginal or vacant sites. By contrast, FBCs identify a palette of mixed-use centers to punctuate corridors and concentrate services within walking distance of residents and for those arriving by other transportation modes. FBCs identify the components; it’s up to the community to choose which components fit best and are most viable in each context.

FBC can’t work with design guidelines guidelines, and complicates staff review of projects. Because conventional zoning doesn’t ask a lot of questions, most planners have had to learn what they know about design on the job, and need design guidelines to fill in the gaps left open by the zoning. That’s how I learned. A well-prepared FBC doesn’t need design guidelines because it explicitly addresses the variety of issues through clear illustrations, language, and numerous examples. However, we are not allergic to design guidelines; the key is to make sure that the guidelines clarify what is too complex, variable, or discretionary to state in legally binding standards.

Final Thoughts

I’m enthusiastic about FBC and regard it as a far better tool than conventional zoning for walkable urban places. However, it’s still zoning, and it needs people to set its priorities and parameters. It needs people to review plans and compare them with its regulations. Having a FBC will require internal adjustments by the planning department and other key departments, such as Public Works.

Form-based coding began in response to the aspirations of a few visionary architects and developers who wanted to build genuine, lasting places, based on the patterns of great local communities. Unresponsive zoning regulations often erected insurmountable barriers to these proposals and made proposals for sprawl the path of least resistance.

From its outset nearly 35 years ago, form-based coding exposed the inabilities of conventional zoning to efficiently address the needs of today’s communities. Today, form-based coding is a necessary zoning reform—one of several important tools that communities need to position themselves as serious candidates for reinvestment.