FBCI Instructor Goes to School for Form-Based Codes

Tony Perez, Opticos Design’s Director of Form-Based Coding, has gone back to school this spring, teaching a graduate-level studio dedicated to Form-Based Coding at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona, CA. While some universities invite guest lecturers to speak about FBCs, Perez’s class, “Form-Based Codes in the Context of Integrated Urbanism,” is one of the only full courses on the subject in the country.

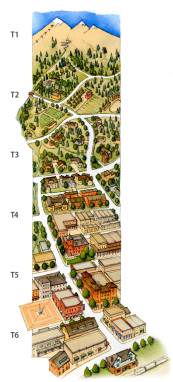

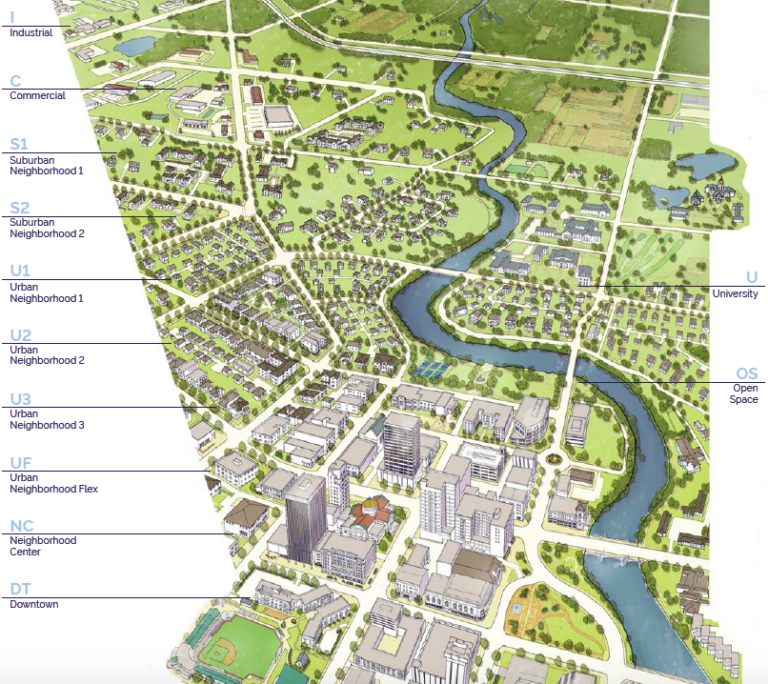

In one of his first classes, Perez introduced his students to the Rural-to-Urban Transect. “Some had heard of it or had seen the famous diagram by Duany Plater-Zyberk, but essentially, the idea had not been fully explained to them,” he said. “It’s really interesting to see students who have little to no training react quickly and positively to the Transect system. They can begin to see how it responds to the world outside, the particular areas that they know well, and that’s very exciting.”

Throughout the spring quarter, Perez will discuss the reasons and purposes for FBCs, where they do and don’t apply, what type of information is needed to write an effective FBC, and how to coordinate an FBC with a community’s public policy.

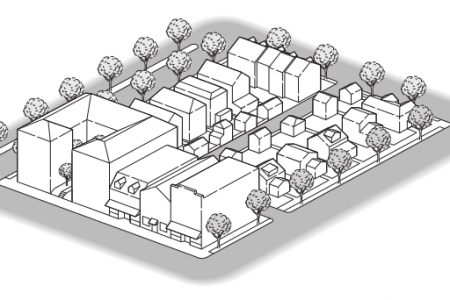

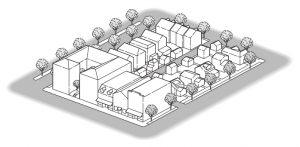

Students will explore the neighborhoods, districts, corridors, and centers of their individual study areas—one-square-mile of a Southern California community—and their relative status and condition. They will work with their study area for the duration of the quarter, focusing on one pedestrian-shed, and will be tasked with developing a vision, policy direction, illustrative plan, and code framework that includes a regulating plan and the implementing zones.

In addition to being an avid FBC advocate, Perez is a motivated instructor. Prior to being invited to teach the new FBC course, Perez served as a guest lecturer at Cal Poly and the Form-Based Codes Institute’s FBC 201, “Preparing a Form-Based Code: Design Considerations,” as well as co-taught a two-semester capstone project class on transit-oriented design and Form-Based Coding at UCLA. “I love to share information and am motivated by the interest I see in others when they get excited about learning,” he says. “We need to help the next wave of people who will move this forward and who can work in more areas than I.”

Andrews University teaches students how to use the SmartCode for their urban design projects while some universities address FBC as part of their urban design programs but do not offer similar courses on FBC preparation. Perez says that a discussion of the physical realities and exciting information about how towns and cities are built—the urban components that comprise each place and the subsets of components that comprise each area and its individual features—is largely missing from most urban planning programs, including when he was in school. That’s how he got started working with FBCs nearly 15 years ago. “When I realized that this tool could see those realities in ways that the current system could not, that was an exciting day,” he said.

At the end of the course, students will be expected to understand the real differences between conventional land use-based zoning and Form-Based Codes, as well as be able to describe the overall process of what one needs to consider when working to apply an FBC to different types of areas. Equally important, he says, is that the students begin looking at the world as it presents itself: as a composite of varied physical components in different combinations that we occupy at different times of the day or night.

Julianna Delgado, Interim Associate Dean of Cal Poly Pomona’s College of Environmental Design and a professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, came up with the idea of a introducing a full course on Form-Based Codes at the school. Delgado says she and Perez got to know each other while attending various FBC-related conferences. “If you want someone to teach something to your students, you ask the best person you know,” she says.

The mission of the California State University system is to train California’s workforce but there are no other formal courses on Form-Based Coding. Delgado says she wants her students to understand that the formal basis for a community is as important as land use—walkability, appropriate architecture, public space and the public realm. “So many communities in California are looking toward FBCs, that giving our students a learning system that is less theoretical and more rooted in practice, would put them at the forefront of the planning profession,” she said.

At Cal Poly Pomona, Delgado says it’s “learn by doing.” Down the road, Delgado imagines developing a studio course that would develop a Form-Based Code for a California community.

“There are many ways to develop this into design courses as well as administrative courses for implementation. There’s a lot that can be done and I’m honored to be able to help the next wave of practitioners,” Perez adds.

Originally published May 20, 2014 on Opticosdesign.com