Strategies For Project Review Under A Form-Based Code

Originally published in Better! Cities & Towns, November 2013.

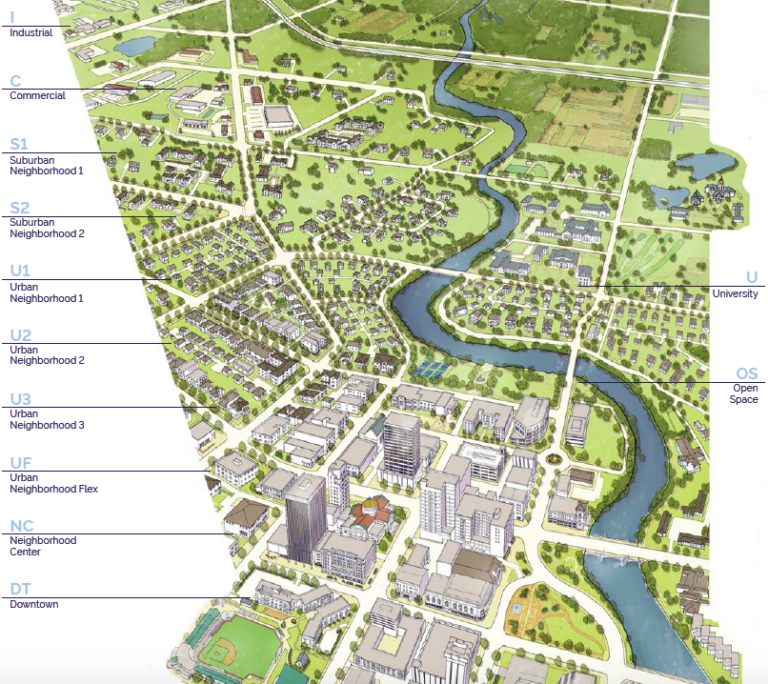

Form-based codes (FBCs) allow communities to implement a plan for quality place- making with a by-right development code, instead of a complicated discretionary design review process. Communities are selecting form-based codes to replace conventional zoning in downtowns and neighborhood centers, not simply to regulate around form instead of use, but also to replace a system of uncertainty with one that offers predictability. By developing graphical standards and prescribing building form, the code can capture the intent of a community’s physical planning strategy.

A community developing a form-based code must determine how it will be implemented and administered.

Still, the art and science of form-based codes continues to evolve to meet the political and design culture of communities. While many cities and towns have determined that they need not have additional project review for development that conforms with the code, others are establishing or streamlining project review systems. Deciding how far to take “by-right” approvals is more complicated than it might first appear. Implementing a form-based code (FBC) is not just a matter of desired form, but also a community’s expectations about the role of government officials, public input into development, and the necessity of architectural design and site plan review. The decision also requires an understanding of what might go wrong, and how unintended consequences and necessary deviations from the code will be addressed.

Many communities have implemented a FBC that requires simple review of projects by a town planner or code enforcement official. But other communities are deciding that, while it makes sense to use a FBC to prescribe the size, bulk, height, lot placement, fenestration, and pedestrian amenities, project review would benefit from an extra look by a staff architect or review board. Further, public meetings may still be required.

A community developing a form-based code must determine how it will be implemented and administered by asking:

- Do we want to review design? While a form-based code will typically regulate form and not design, the community must determine if design creativity should be left for developers and their designers, or reviewed and/or approved by a staff member, town consultant, or local review board.

- Does our community demand public meetings before development review? While the community should already have consensus about building form, height, and bulk (as the code was developed) sometimes neighbors will still expect to be involved in the process of individual project review.

- Can the local community of builders understand and design to the code? It may benefit both the community and the builders to have the assistance of a professional from within the review agency, especially with a code developed for an existing area where individual landowners will need help with both new and existing development on their property.

- Can the zoning reviewers understand the intent of the FBC? Sometimes, the individuals in government who review projects under conventional codes are not the right ones to review projects under a form-based code.

- What, if any, state enabling laws apply? Some state rules require certain levels of notice and/or review under zoning enabling or environmental regulations.

Five different strategies used by communities looking to review projects under a form-based code.

The Appleton Mill Renovation was granted a “certificate of consistency” after a quick review under the Hamilton Mill Canal District code. Courtesy of George Proakis.

The town architect

Employing a town architect is a common practice in implementing a form-based code, particularly in communities that do not otherwise have staff with the time or design skills to undertake the role. Both the town of Hercules and Redevelopment Authority in Contra Costa County (both in California) hired a firm on a contract basis to serve as Town Architect to do code compliance and design review. Other communities have hired a staff person to fill the role. Either way, a Town Architect serves to ensure that development under the code meets both the letter and the intent of the regulation. For a Town Architect strategy to be effective, a community must be willing to place trust in a professional designer to make decisions that will influence the results in the area under the code.

Consistency Review by an Interdepartmental Team

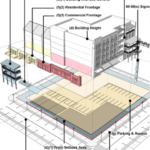

In the Hamilton Canal District in Lowell, Massachusetts (where the author was part of the FBC development team), the City deter- mined that projects should have a straightforward approval. But, zoning was typically approved by building inspectors (as required by state law in Massachusetts) without familiarity with the functional standards and building forms in a FBC. So, the City added a “certificate of consistency” to be provided by a three person board of city planning and building staff, to ensure that a project was compliant. Upon making that determination, a build- ing permit would be issued. The review takes less than 30 days and a permit can quickly be issued for a complying project.

Design review committee

Some communities, such as Ventura in California, have used their design review committee (DRC) to do review of projects under the code. The board does more than determine consistency; it ensures that the architecture of the building reflects the high standards expected by the com- munity. A process such as this can also allow for public comment on a project before construction. While the Board can demand improvements to project design, the project remains a by-right project. Unlike discretionary permit approvals, the DRC does not have jurisdiction over building envelope, site design, or use. The DRC may also grant warrants (minor deviations from the specific requirements of the code as long as they help further the code’s intent), but more significant exceptions require further review.

Penrose Square, above, includes 200 units, retail, and a supermarket. It was approved as a large project under the Columbia Pike code. Credit: Brent VA.

Two-tier Solutions

Arlington, Virginia, developed the Columbia Pike code with a two-tier process. Projects on small sites have a 30-day administrative review, similar to the strategy in Lowell. Larger projects have a 50-day review, with a design re- view and public meetings before the Planning Commission and County Board, similar to the process used in Ventura. Planners in Arlington caution that, despite these short timeframes, the actual steps to prepare a proposal that meets the code and also meets building and fire code and public access requirements is longer. So, an individual project must be ready to enter one of these two tiers before the clock starts ticking.

State-Mandated Solutions

New Hampshire, a state with a long tradition of direct democracy, has a state law requiring projects over a certain size to be reviewed with a public hearing. So, when the New Hampshire town of Dover developed a form- based code for its downtown, all but the smallest projects require public review. Nonetheless, hearings within the form-based code area are much more efficient because of the code. As these examples show, strategies for code implementation depend upon many factors, and selecting a strategy is fundamental to developing, securing and managing a successful code.